Planting in Babylon Pt. 2

Maybe I’m not over it. Maybe the choice to start by telling this story is proof that it still bothers me. Still. Even if I’m “in my feelings,” I’m convinced he missed the point. Several years ago, while still in grad school, I submitted a paper on a model for multi-cultural congregations that I was quite proud of in the end. I had worked hard on the paper and included a theological argument for diversity I thought was soundly reasoned. When I got it back from my favorite professor, it included this feedback:

“I am puzzled why you have turned to the Exodus narrative to emphasize the multiethnic nature of God’s redeemed people. Why not [use] the NT passages that more explicitly emphasize … God’s design of making His church multiethnic and its theological significance?”

This question is at the heart of this article. I believe God’s plan was always about making a mestizo people that would reflect His character on earth by making the world as it should be – a place of beauty, justice, and goodness. People failed to do this time and time again, but that doesn’t change the plan. He is redeeming a mixed multitude and calling them to create, to plant gardens, and build communities that set things right and restore His order. If this was always His plan, then it should be seen in the story the first time He rescued people and called them His own. In fact, the identity of Israel should hint to God’s plan for a multiethnic people just as the Church finally displays it. And, it does.

Returning from Exile

At the end of part one of this series, I noted the promise God made to Israel while they were exiled in Babylon. He said, “I will gather you from all the nations and places where I have banished you, and will bring you back to the place from which I carried you into exile” (Jer. 29:14). This promise reveals a second important identity marker for God’s people. The first was our non-innocence, our inability to work in Babylon as self-righteous missionaries detached from the city. The second is our mestizaje, our mixed identity as one chosen nation, a royal priesthood called to reveal His character (1 Pet. 2:9). We do this in our work (which will be explored further in the final part of this series), but we also do this in our very existence as a community. This is the focus of this article, and with all due respect to my former professor, the best way to show the importance of our mestizaje is to start at the beginning of the story.

The first time God rescued a people from slavery and called them His own, he rescued a mixed multitude (Exod. 12:38). The exodus story – the story of how the Lord rescued Israel from slavery to Egypt by sending Moses as His messenger – is essential to understanding how salvation happens in the Bible, what it means, and what it does to those who are saved. The Exodus was a significant part of ancient Israel’s history and identity.[1] It shaped their understanding of God and His works of salvation.[2] In fact, every time salvation happens in the bible, it’s meant to be understood as an echo of the exodus, a “new exodus,” a repetition of the pattern set in Egypt. While in exile, Israel waited on God to rescue them yet again in another powerful exodus that would bring them back home to their land. However, when they finally did return home, they quickly realized they had not yet been fully freed, and the exodus pattern remained unfinished. That is how the Old Testament ends, but for the careful reader paying attention to the pattern, the start of the New Testament should thrill because it introduces a new Moses, Jesus of Nazareth.

The writers of the New Testament, being faithful Jews, framed the story of Jesus as a great exodus. N.T. Wright argues that in the letter to Ephesus Paul is using the phrase, “guarantee of our inheritance” to draw from the themes of the Exodus narrative.[3] According to Wright, Galatians chapter four is part of a larger thought-unit “of the rescue of God’s people and the whole world from the ‘Egypt’ of slavery.” He observes clear “exodus language” in Galatians 4:1-7 that is echoed in Romans 8:12-17. He goes on to say, “by overlaying that great story across the even greater one of the accomplishment of the Messiah, rescuing his people from the present evil age, Paul is able to say… this is therefore how you are rescued from sin and death.”[4]

If the exodus is this important to our understanding of all the salvation acts in the Bible, especially the way we understand Jesus’ acts in saving the Church, then the details of Israel’s salvation identity should inform the way we read Paul and other NT writers’ words about the multi-ethnic makeup of the Church. Precisely for this reason, Exodus chapter 12 verse 38 can’t be glossed over. At the very least, the mixed multitude of Israelites who left Egypt as God’s people included the half-Egyptian children of Joseph that formed the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh. That means that “Israel” included some who had the blood of their oppressor. The verse says that a “mixed multitude also” (emph. mine) went with Israel. This suggests that other non-Israelites-by-blood went out of Egypt as part of God’s people. The instructions that follow Israel’s exit assume this mixed group.

The first instructions are for the Passover meal which commemorated God’s rescue of Israel from slavery. In these instructions God includes this accommodation: “A foreigner residing among you who wants to celebrate the Lord’s Passover must have all the males in his household circumcised; then he may take part like one born in the land … The same law applies both to the native-born and to the foreigner residing among you” (Exod. 12:48-49). This instruction, including its details about circumcision, and the ones that immediately follow are all about marking the identity of Israel. They make clear who belongs as part of God’s people. For instance, the next instruction is for a memorial that would be celebrated on the new calendar God gave them (see 12:2; 13:3-9). Holidays were established for Israel to remember who they were as the rescued slaves that were now God’s people.

The New Exodus

As the greater Moses (Heb. 3:3), Jesus accomplished a greater exodus. Therefore, the mixed multitude of Israel is only but a hint of the mestizaje of the Church. Like any biblical theme, the mixed identity of Israel grows more complex yet clear as the story continues. By the time Israel was exiled in Babylon, Ruth the Moabites had married into Israel. Rahab the Jerichoan prostitute joined the nation. These are only two examples of the many times Scripture makes clear that “Israel” is a complex name for a mixed people belonging to the Lord. When Jeremiah writes his letter to the exiles, he reveals that the Israelites were going to experience another mestizaje. They wouldn’t return to Israel exactly as they had left it. They would now bring back some of Babylon with them.

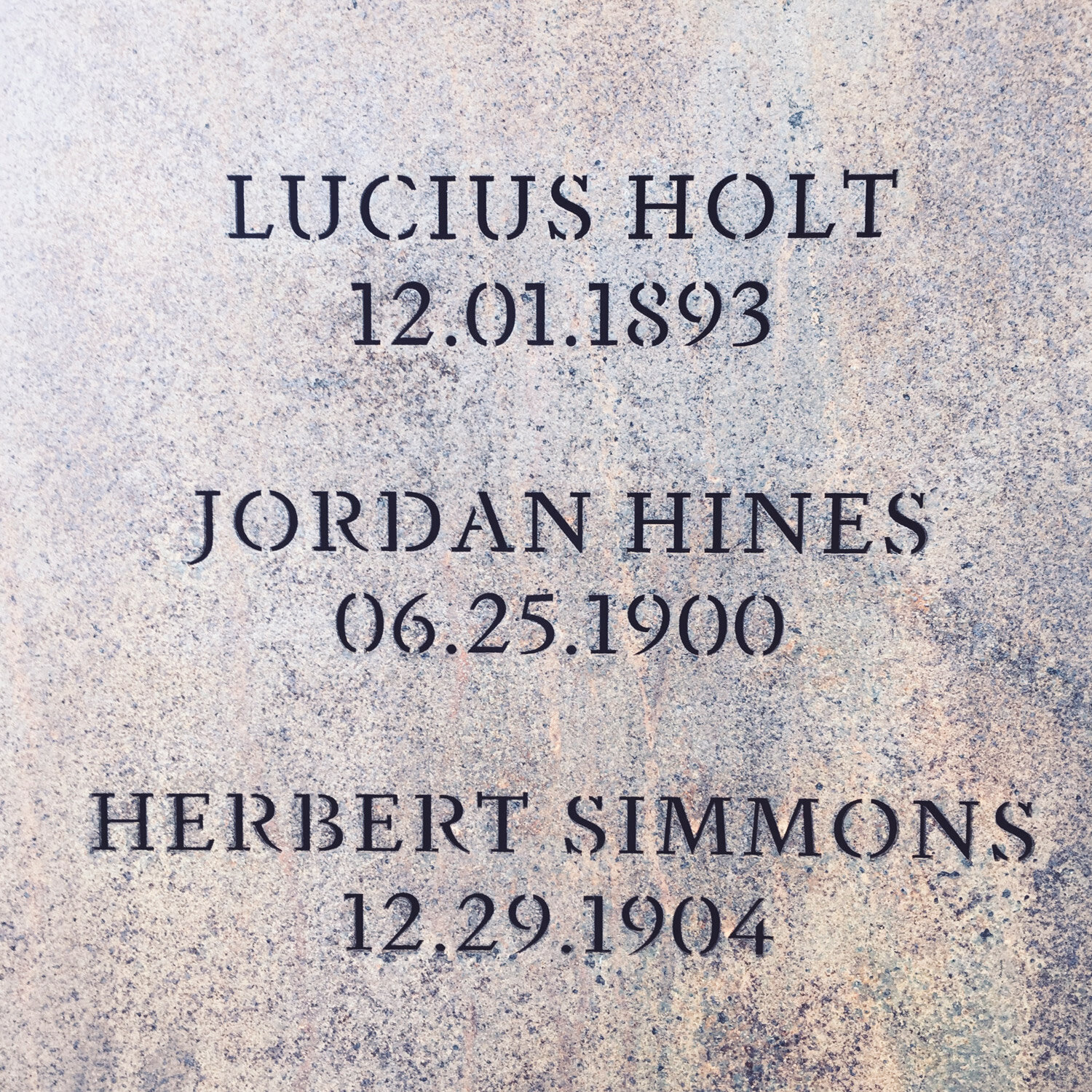

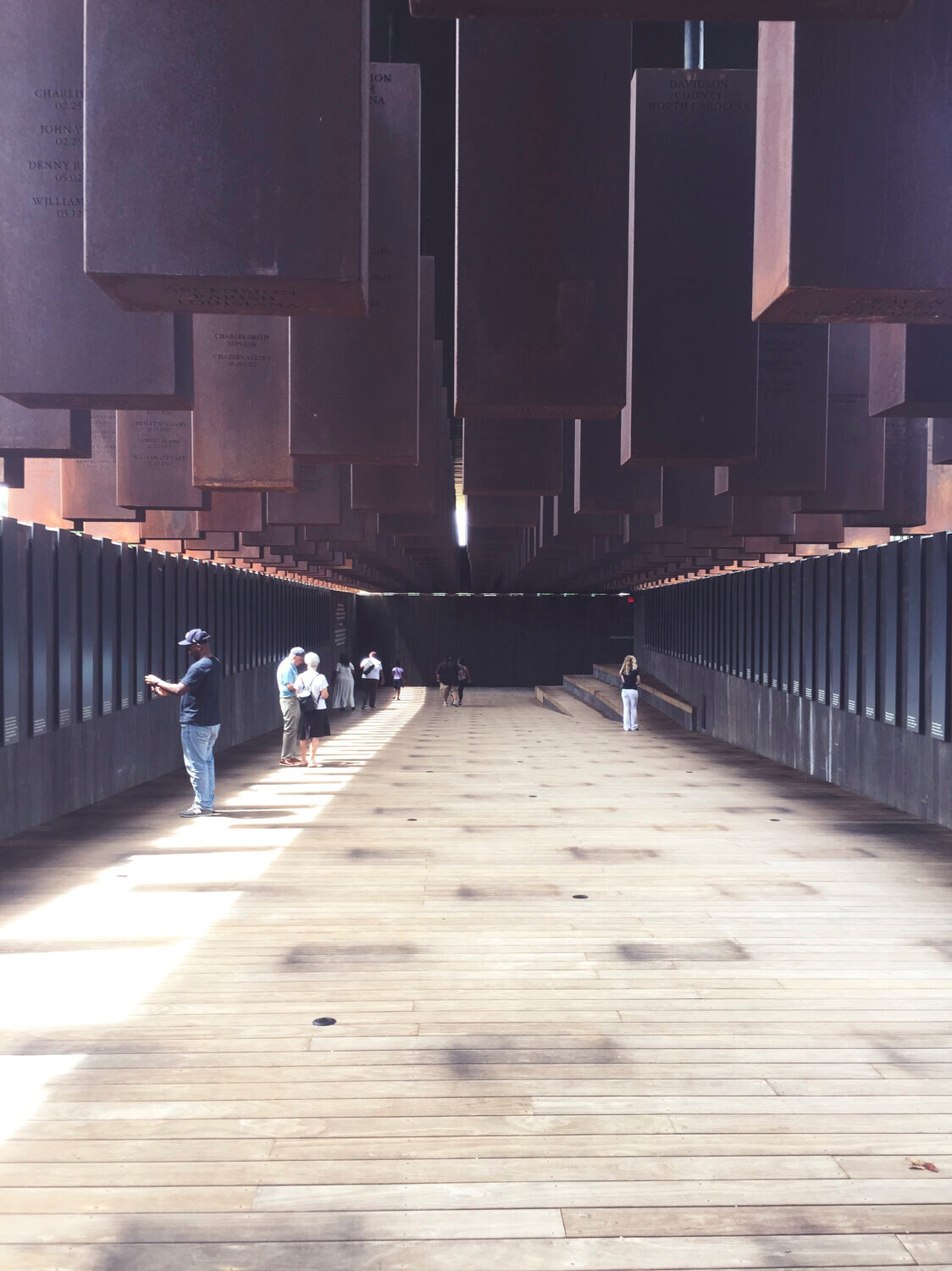

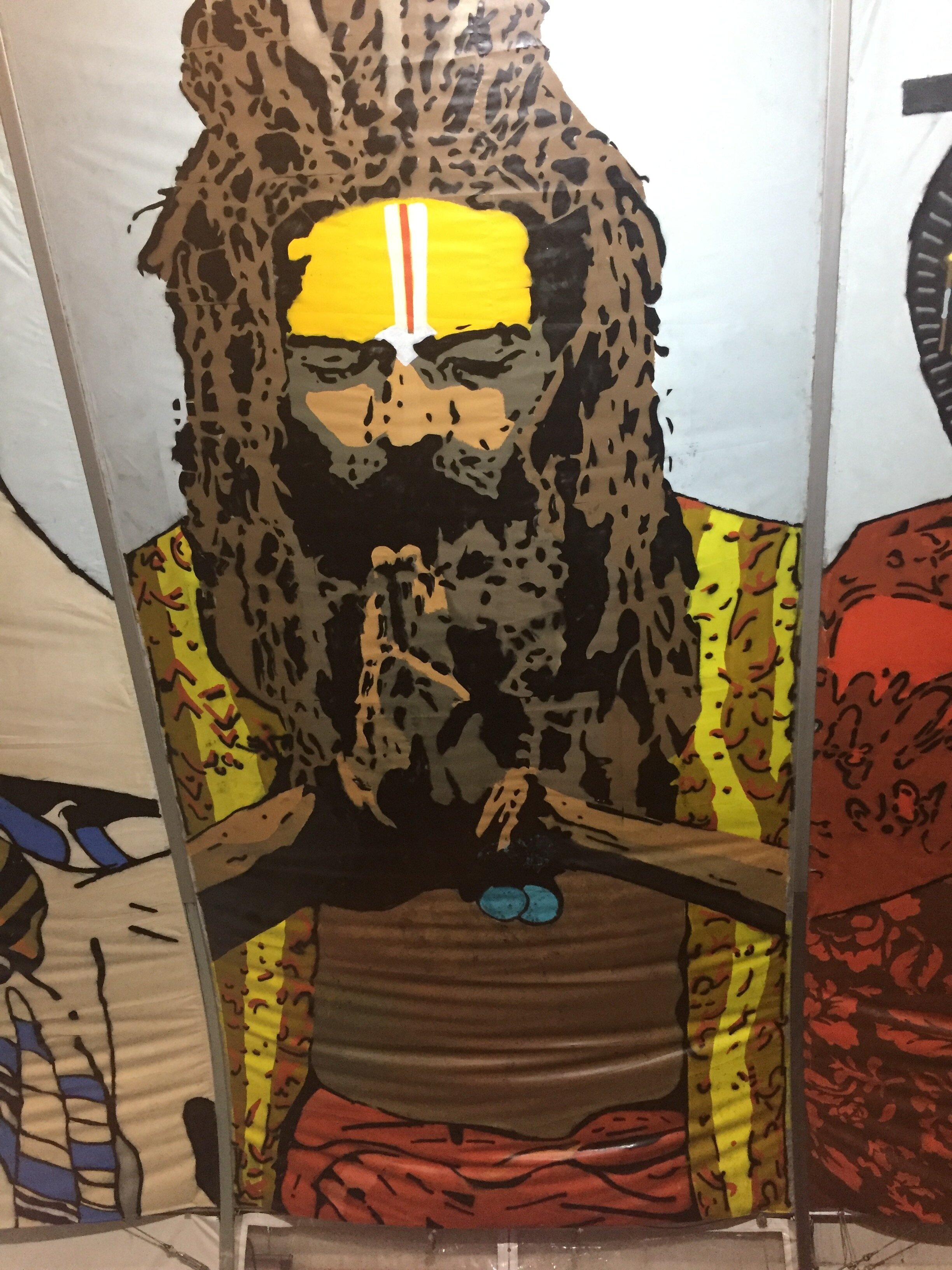

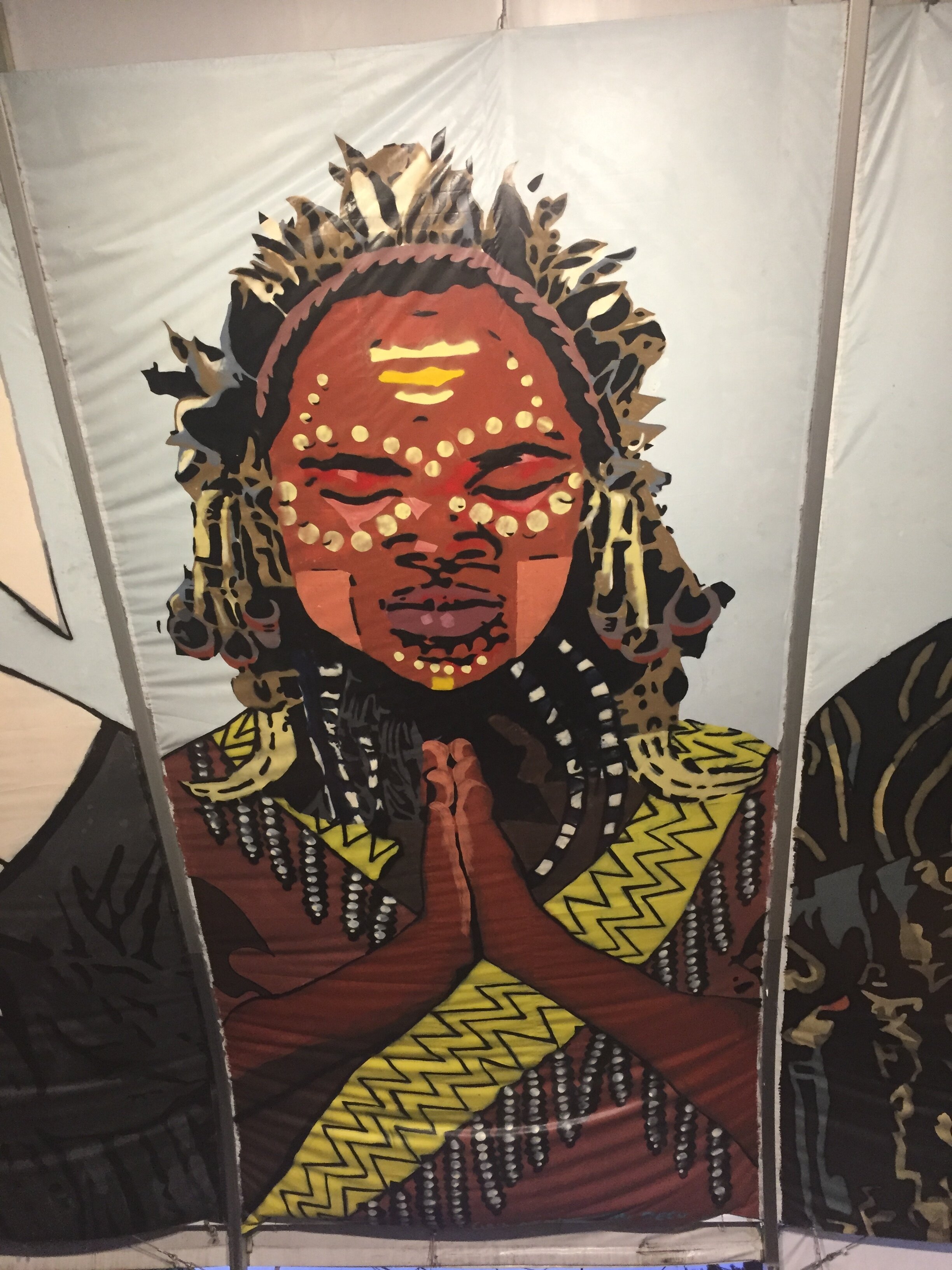

The Lord’s instructions to the Babylonian exiles was to plant gardens, build homes, and marry off their children. They were to become part of the fabric of Babylon. It was there, as members of the city, that the Jewish community developed synagogues. It was there that they developed new cultural rhythms that would mark them as God’s people. When Jeremiah, on behalf of the Lord, writes, “I will gather you from all the nations and places where I have banished you, and will bring you back to the place from which I carried you into exile” (Jer. 29:14), he is hinting that Israel would be a land of diverse experiences with a new Israeli community that now includes cultural expressions from nations abroad. Indeed, this is seen today. In Jerusalem, near the old city, there is a series of banners along a popular bike/walk path that display people from many ethnic groups in a prayer position. The text below the banners reads, “One of the most important visions for the city of Jerusalem is its existence as a cultural and religious center for all peoples.” The banner then quotes another prophet, “for my house will be called a house of prayer for all nations” (Isaiah 56:7).

Jesus was born a Jewish man in Israel while it was under Roman rule. His experience, his cultural context, included yet another mestizaje where Roman culture played a significant role. As the new Moses, He accomplished the greatest exodus of all, and through His death and resurrection, those who follow Him are part of the greatest mixed multitude to be saved from slavery. He is fulfilling that promise written by Jeremiah and more. There is one final theological contribution from the Exodus story. Peter Enns comments that the Exodus pattern is closely aligned to the new creation theme. According to Enns, “to redeem is to re-create.”[5] God, in recreating a people of a mixed identity, is now calling them to care for and develop a culture that reflects the world as He intended it. This is the subject of the final part in this series. For now, may we live in Babylon as one beautiful display of God’s unifying love for all people. Together, we are His holy nation, His Church.

Footnotes

[1] Ronald S. Hendel, “The Exodus in biblical memory,” Journal of Biblical Literature 120, no. 4 (2001) 601 [601-622].

[2] Otto Alfred Piper, “Unchanging promises: Exodus in the New Testament,” Interpretation 11, no. 1 (January 1, 1957) 4 [3-22].

[3] Wright, Simply Christian, 125.

[4] Wright, Justification, 136. See also pg. 157-158 point 4, where Wright argues the Exodus slavery language is part of the summary of Paul’s theology

[5] Enns, New Exodus, 216.

![CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=937608 [5]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5dfd8beb22732d3b23495b1f/1577989241484-HKVUQ3DOPNPRI92VFOG4/Adams_onis_map.png)