What you missed in the “Halftime Show was Inappropriate” Debate

What happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object? If this paradox were possible, it would be about Latina music and fashion in the US. The unstoppable force of Latina hips as they gyrate to the rhythm of dembow, salsa, and champeta would crash like hurricane winds against the fortified opinions of white America’s glass house. On Sunday, Feb. 2nd, the paradox was on full display when Shakira and J.Lo became the first Latina singers to headline the Super Bowl halftime show. The debris of opinions scattered all over Twitter and Facebook are the unavoidable aftermath from this collision. On one level, that may have been the desired effect of a performance as culturally centered as this one, but on another, the opinions trending online reveal deep undercurrents of racism, cultural myopia, and some problems with woke culture. Here are three key points where the conversation went wrong and a proposal for new dialogue.

Modesty Standards and Whiteness

Whiteness is a loaded word; I realize that it strikes many readers differently. For my purposes, whiteness is not about pigmentation. I am not referring to people with lighter skin tones. In fact, no one has ever been white, and there are many Latino/as with light complexions. I use whiteness as the name for the racial system here in the US and in other countries affected by colonization. Whiteness has theological underpinnings and is supported by bad science. It is rooted in the idea that physical differences gave inherent, God-given, superiority to Western Europeans, their descendants, and their way of life. As a system, whiteness continues to promote this singular culture, forcing all others to conform to it. Much of the conversation regarding this year’s halftime performance reflects the way the system (what I am calling whiteness) shapes our experience.

Many viewers felt as though the half time show was a “racy, vulgar, and totally inappropriate performance.” These opinions mostly focus on the clothing and movement styles of the Latina performer, and they usually reduce the performance to a display of erotic sexuality meant to arouse. However, this perception of the performance drastically misunderstands the differences between Hispanic and “White” culture. These opinions either reflect a polarizing posture toward cultural difference that overly romanticizes one’s own culture (in this case, white culture) and overly criticizes the other culture (in this case, Latin American culture), or they could reflect a minimizing posture toward cultural difference that assumes that all cultures operate under universal rules for modesty, displays of human sexuality (particularly female sexuality), and dance.

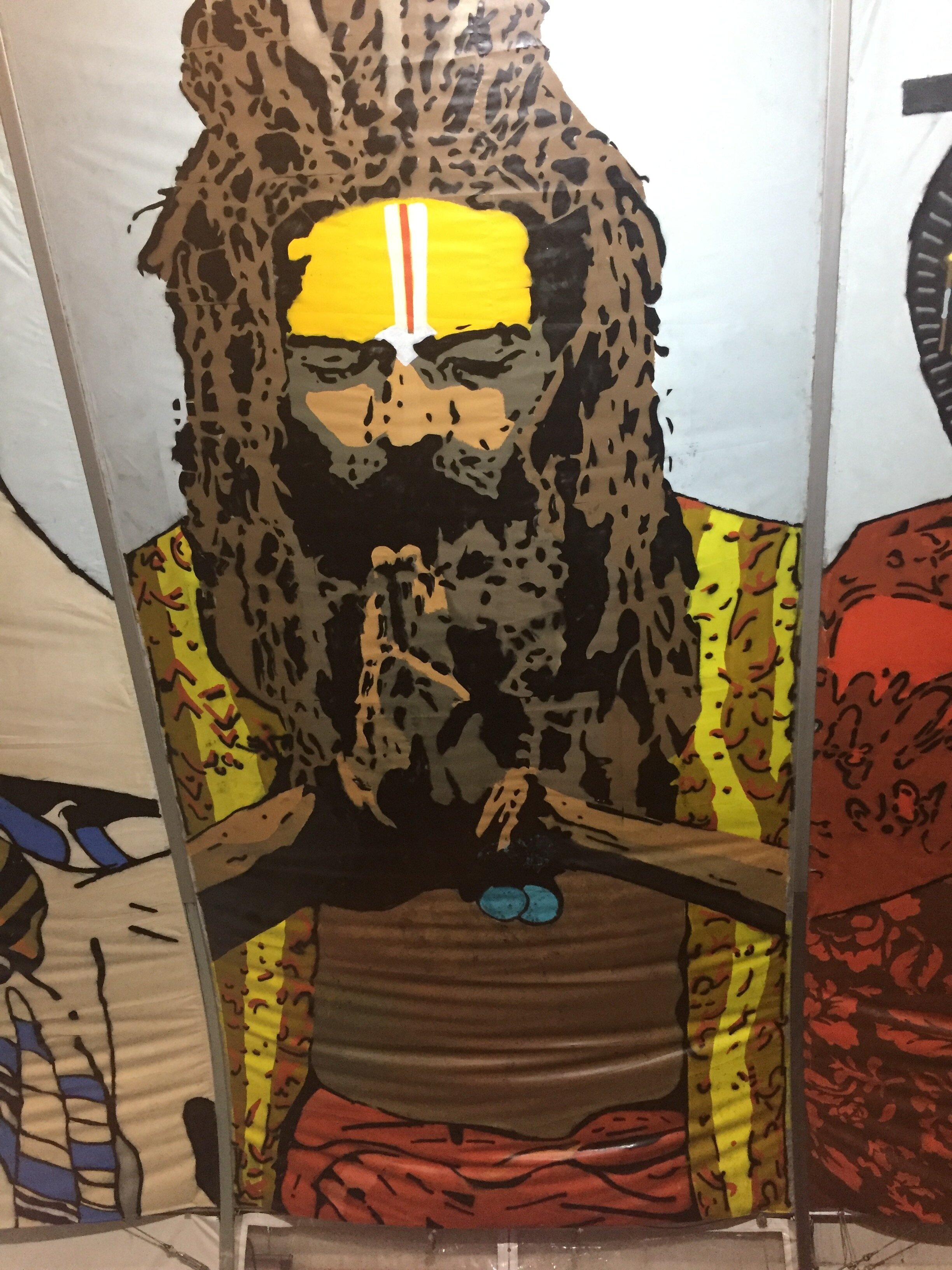

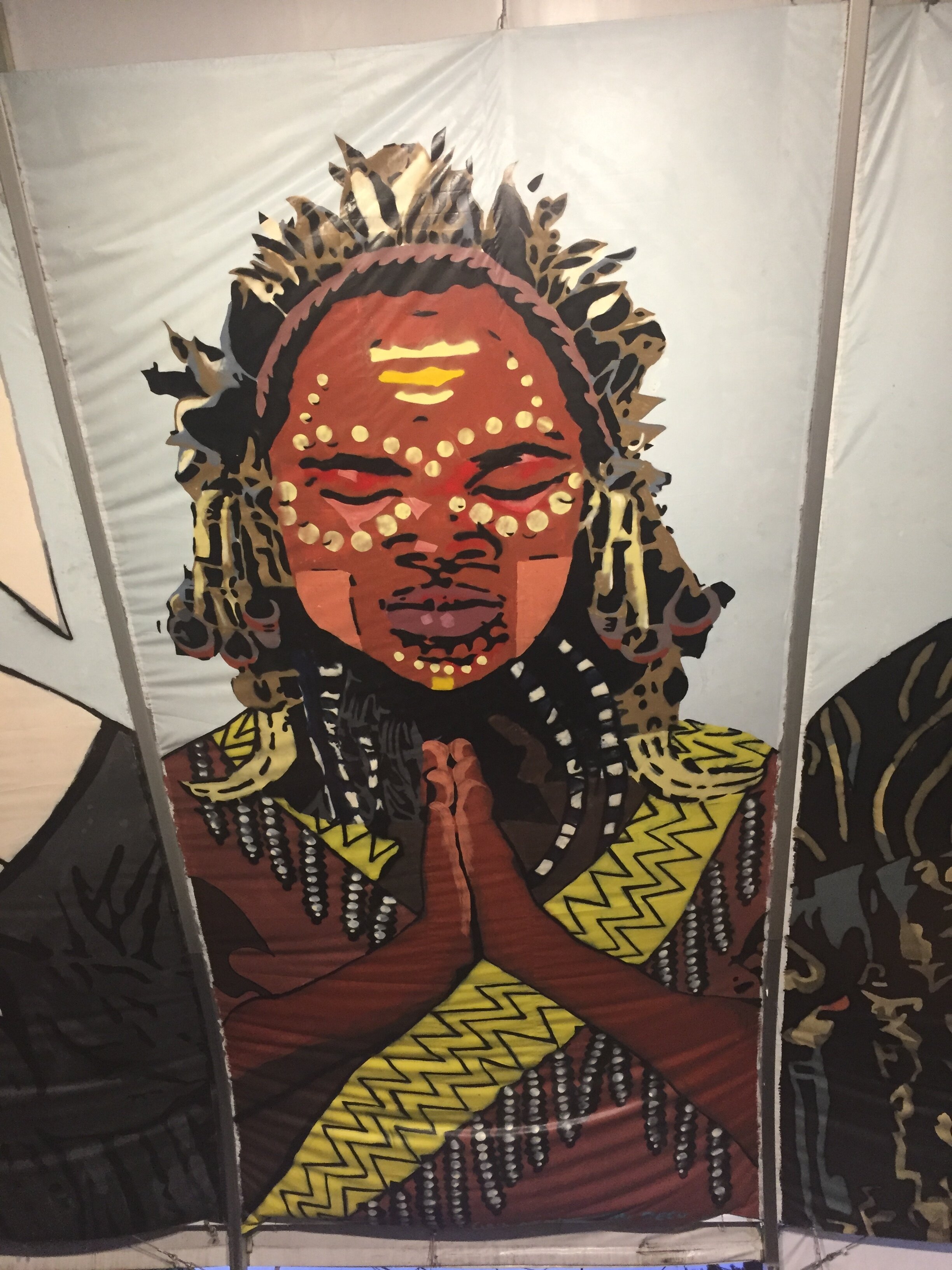

The differences between the two cultural worlds reflect a network of values, beliefs, and assumptions about the body and its meaning. What does it mean to demonstrate technical skill in rhythmic, Afro-Latin dance styles? What does it communicate to move our bodies in outfits that accentuate the movements? How should it – Latin dance in Latin clothing – be understood? To answer these questions, we need a dialogue about female bodies that is not framed by whiteness. We need a conversation where the terms match the subject. At present, the majority response to the halftime show suggests we do not fully know what to make of Hispanic female bodies.

The Big Picture

In most cases where pop-culture events cause controversy, people zero-in on a specific moment that epitomizes what they appreciated or what displeased them. This event did the same. In many of the reactions for/against the halftime show there appears to be a handful of moments that standout. The most meme-able of these moments was Shakira’s zaghrouta, a sound made by sticking out one’s tongue and letting out a high-pitched sound which is common among women in the Middle East expressing joy or other strong emotions. (Shakira is of Lebanese descent). There was also J.Lo’s brief dance on a pole, something that no doubt was incorporated after her grueling training in preparation for the Hustlers movie. These two, among other moments from the show, were cause for critique and dismissal. In response, however, many have argued that the focus is wrongly placed. Instead, they propose the emphasis should be on the choir of children displayed in cages as J.Lo’s 11-year-old daughter, Emme, led them in a rendition of “Born in the U.S.A.” [1] This, they counter, should be the focus of the event because it sends a powerful message about the border crisis.

In both arguments there is a flaw. No event, much less one as packed with symbols and meaning as this one, should be reduced to a single moment. Instead, the event must be interpreted in its totality. The viewer must ask questions about how each moment and symbol contributes to the meaning of the other. Once done, the viewer should decipher a theme, and they should consider how each symbol contributed to it. To understand the theme, the viewer should also explore the world behind the event. What factors led to Shakira and J.Lo being the first Latina’s to headline the halftime show? What might have inspired the choreography and setting of the show? How do these antecedents affect the way the viewer reads the event? This performance, as any pop-culture product, must be interpreted as a complex whole rather than be reduced to a simple flashpoint.

The Black/White Binary?

There is a third current of discussion worth reviewing here. In the many reactions that flooded Twitter after the Super Bowl Halftime show, Jemele Hill’s exemplifies a response that may implicitly communicate two assumptions worth challenging. Here is her tweet:

The language of crucifixion aside, Hill’s point seems to be that black woman had to pay a price, pave the way, for Latinas to now thrive. It also may imply – though it is worth emphasizing that it also may not – that Latinas are reaping a reward that is not their due. While Janet Jackson did have a role in the start of J.Lo’s career, the point may be overstated. First, it implies a bad binary. It is possible that those who are making this argument are still working from a black/white binary that requires all acts of social progress to come from one of these two “archetypes.” This, however, misunderstands the role Hispanics really have in the fabric of American culture. I dealt with this in a previous article, but my thoughts can be summarized this way: we cannot make sense of race in America by using two categories. These Latinas have women in their own heritage that contributed to their success. Women like Selena, Celia Cruz, and Gloria Estefan all contributed to the foundations of Latina celebrity that J.Lo and Shakira now embody so fully. The Latina contribution to progress in pop-culture should not be reduced just as the African American women’s contribution should not be overemphasized. Progress is not zero-sum. The success of Latinas only contributes to the overall reimagining of American society without taking away from the success of African American women.

Reimagining America con Salsa y Sabor

The halftime show included one moment that caused some viewers, especially Latinos, brief anxiety. While her daughter Emme sung “Born in the U.S.A.,” J.Lo reemerged on the stage wearing what appeared to be an American flag. After joining her daughter in the song, J.Lo opened the flag to reveal that it was double-sided, displaying the Puerto Rican flag on the inside. This symbol, in the context of the whole show, reimagines the US-American identity, putting a new proposal on center stage. The NFL Super Bowl is an US holiday, and the NFL has recently been the stage for conversations about what it means to be a US-American and even patriotic. This year’s halftime show added to the conversation by reminding us that mestizos are American, and Americans are mestizo. Shakira and J.Lo put their mestizaje on full display by singing in Spanglish, honoring their heritage in the Bronx, Baranquilla, and Lebanon, and dancing in Afro-Latin styles. They showed the world that there never really was a paradox. They were unstoppable. Now we have to be movable. Join their dance and the new world that it imagines.

Footnote

[1] It’s worth noting that as an 11-year-old, Emme lives in an America that is remarkably different from her mother’s version. Non-Hispanic whites already are less than 50% of the youth population in 632 of America’s 3,142 counties. According to research published by National Geographic, 2020 was projected as the year when 50.2% of American children would be from today’s minority groups. “As America Changes, Some Anxious Whites Feel Left Behind,” Magazine, March 12, 2018, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/04/race-rising-anxiety-white-america/.