“Negro soy desde hace muchos siglos” - Jorge Artel[1]

I was 10 years old. I was living in this country for about a year in Washington Heights. Washington Heights is a mostly Dominican and Puerto Rican neighborhood in Manhattan, NYC. There, through the many Latin@ kids I met while in school, I realized I was part of a larger community of Latin@s. My experience outside of NYC, specifically in Hackettstown, NJ, a small town in central New Jersey, reminded me of another important part of my identity. There, I briefly lived with some close friends of the family while learning to acclimate to the U.S. I knew very little English, and some of the boys in my Sixth-grade class invited me to play a game of American Football. My team won. I don’t know how, but according to one of the boys from the losing team, “You only won because you have the nigger on your team.” I, without knowing a word of English or any of the customs here, could not understand why a fight suddenly broke out amongst the boys with whom I played, but what triggered it was the word nigger and everything it means historically in the United States. Not only did I learn English very quickly then, but that’s when I began to understand myself as holding multiple identities here in the U.S., not only as a Colombian boy, as a Latino boy, but also as a Black boy, an Afro-Latino boy.

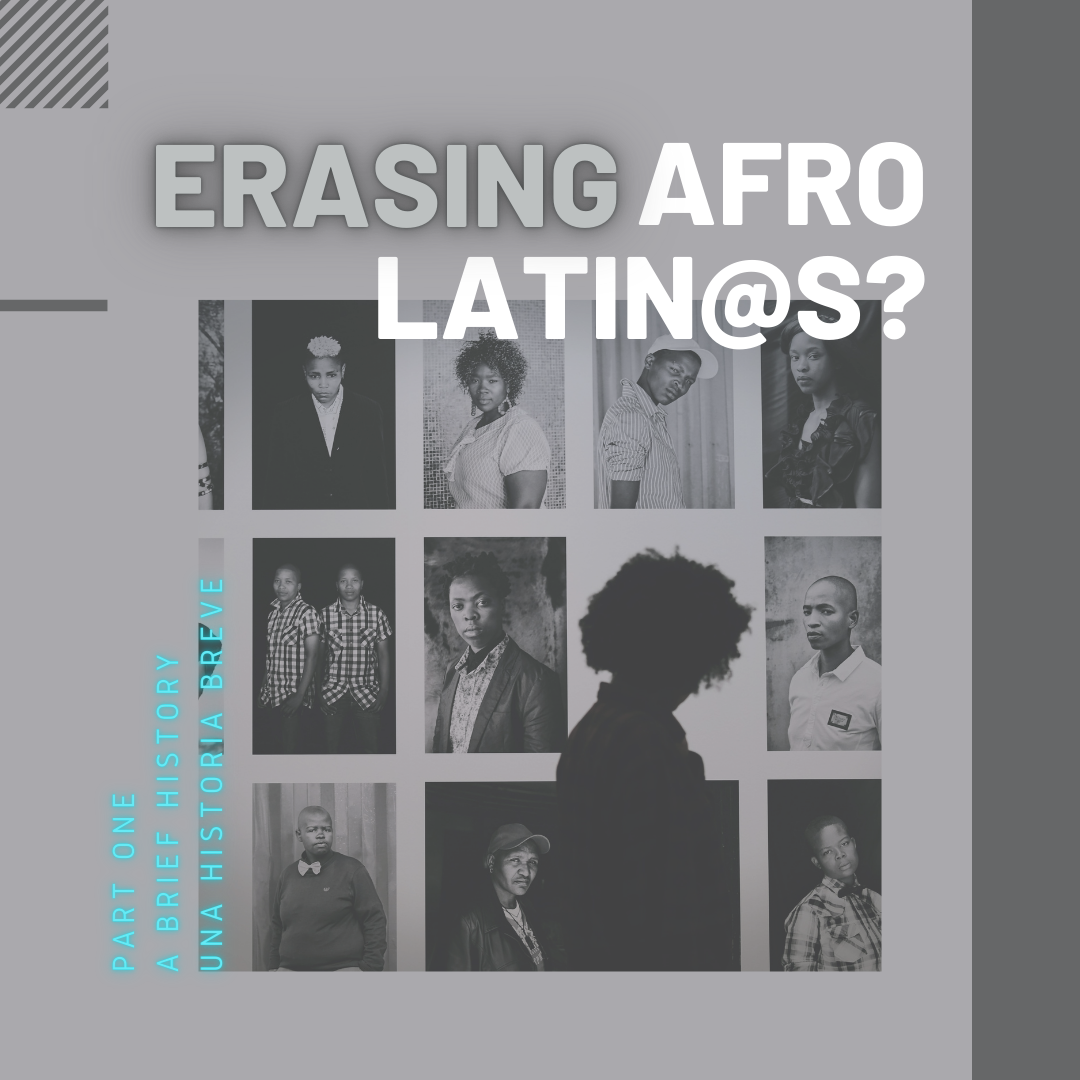

Afro-Latinidad is an identity that some claim to be new, a term that some misunderstand as trendy, or an idea that people think is novel, but it is more properly understood as a word that became representative of an implicit conceptualization of Blackness amongst Latin@s that has been around for decades. The reality of Afro-Latinidad is that it is not simply a concept or a term. If we are to only focus on the specific time where this term was coined, we would have an incomplete understanding of Afro-Latinidad. Afro-Latinidad is a lived experience that has been a part of the Latin@ identity for centuries. Simply defined, Afro-Latin@s are “people of African descent in Mexico, Central and South America, and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, and by extension those of African descent in the United States whose origins are in Latin America and the Caribbean.”[2] However, as simple as this definition may seem, a consensus of the term has been difficult to standardize:

“Afro-Latin@? What’s an Afro-Latin@? Who is an Afro-Latin@? The term befuddles us because we are accustomed to thinking of “Afro” and “Latin@” as distinct from each other and mutually exclusive: one is either Black or Latin@.”[3]

To some members of the Latin@ community, one can be either Black or Latin@, but not both.[4] This false dichotomy led many people today to think that Afro-Latinidad is a recent phenomenon when, in reality, the study and experience of Afro-Latinidad have been a part of the Latin@ identity since its origins.

“Generación tras generación, la humanidad ha enseñado una historia falsa; una historia que excluye las contribuciones de la comunidad africana y sus descendientes.” – Arturo Alfonso Schomburg[5]

A little over a century before my own racial incident in Hackettstown, another young boy from Santurce, Puerto Rico, was also told something that would change his life trajectory. Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, born in 1874, was in grade school when he asked his teacher why there were no mentions of Black people’s contributions in his books. His teacher replied that it was because Black people had no history.[6] A young Arturo decided then to dedicate his life to collecting and researching everything he could about Black people’s history throughout the Diaspora. This led to the creation of one of the most internationally acclaimed research centers for the study of people of African Descent from all over the world.[7] While not credited with creating the term Afro-Latin@, it is undeniable that Schomburg’s personal experience is as an Afro-Latin@. As someone who self-identified as Negro and Puertorriqueño, his collection, research, and studies of the African Diaspora and its ties to the Americas led to the beginning of a more comprehensive understanding of what we today call Afro-Latinidad.

The term Afro-Latin@ has been used loosely in one form or another since around the 1970’s, it was then that the U.S. Census asked residents to select their racial category in addition to their Hispanic identity.[8] But the use of the term as empowerment for an understanding of Black Latinidad comes from a Diasporic understanding of Blackness. This is specifically highlighted by Prof. Miriam Jiménez Román:

“The concept of an African diaspora, while implicit for decades in this long historical trajectory, comes to the fore during these years [1980’s] and serves as the guiding paradigm in our times. Most importantly for our purposes it acknowledges the historical and continuing linkages among the estimated 180 million people of African descent in the Americas. Along with the terms “Negro,” “afrodescendiente,” and “afrolatinoamericano,” the name Afro-Latin@ has served to identify the constituency of the many vibrant anti-racist movements and causes that have been gaining momentum throughout the hemisphere for over a generation”[9]

We cannot trace the beginning of the term Afro-Latin@ to a specific moment or a specific person, but rather it is a term that expresses a lived identity that has been in the Americas for centuries. Furthermore, the term Afro-Latin@ is a result of transnational conversations between people of African Descent; it is a derivative term that comes to the United States from Latin American anti-racist movements and other pan-African movements in the world. It is important to note that the term, as important as it is, is centered in the United States and it is chiefly used to describe a reality of Latin@s of African Descent in the United States. In Latin America the term Afro is usually linked to a national understanding of one’s identity, namely Afro-Colombian, to describe someone who is Black and Colombian. However, in the United States, as the pan-ethnic term Latin@ became normalized to define a multi-ethnic people, it was necessary to create a term that highlights individuals of African Descent who are Latin@s.

Through research, started by Schomburg but continued by countless others, we realize that Afro-Latinidad is not just a term, rather, it is a lived experience, an identity, that has permeated all aspects of Latinidad. This identity, with or without a term, has roots very early in the history of the Americas[10] and has been developed and preserved through various means –those recognized by academia and those not– that served to awaken us to the reality, resistance, and permanence of Afro-Latin@s in a culture that had created a pigmentocracy to erase all vestiges of Blackness.[11]

The lived experience of Afro-Latin@s, whether here in the U.S. or in Latin America, was not preserved exclusively via written texts and other works that subscribe to a specific anthropological and archival ideology. Rather, Afro-Latin@ customs were preserved throughout the centuries via a variety of traditions, whether oral, musical, or gastronomical[12], serving to remind the world of the visibility and presence of our community both here and afar. This is important to note because the current diverse expressions of Afro-Latinidad here in the United States and throughout Latin America are emblematic and consistent with the way that Afro-Latinidad has been preserved and proclaimed for centuries.

Novels depicting quotidian Afro-Latin@ life, such as The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz and Soledad by Angie Cruz; comic books depicting Afro-Latin@ superheroes, such Miles Morales: Spider-Man; books informing the Afro-Latin@ experience in the U.S., such as From Bomba to Hip-Hop by Juan Flores; and music performed by a variety of artists from all of the different genres influenced by the African Diaspora (salsa, merengue, reggaeton, tango, cumbia, etc.), such as Ismael Rivera, Grupo Niche, Machito and His Afro-Cubans, and Tego Calderón. All these artists that write and perform songs indicative of an Afro-Latin@ experience should be considered essential when thinking of how an Afro-Latin@ expression of identity exists in multiple dimensions over time and place.[13]

In addition, many organizations and institutions have consistently emerged since Schomburg’s research and collection began to challenge a white supremacist historical record. We do not have the space here to account for all of these, but we can consider some contemporary organizations that study Afro-Latinidad as emblematic of the continuation of this line of study. Organizations and institutions such as the AfroLatin@ Forum in New York City, Encuentro Diaspora Afro in Boston, and the International Society of Black Latinos in Los Angeles continue the legacy laid by Schomburg. Other grass-roots efforts focused on expanding the visibility of Afro-Latin@ culture such as Latinegras, the Black Latina Movement, the Afro-Latin@ Festival; blogs such as Ain't I Latina and #IAmEnough all point to the same idea, that the Afro-Latin@ experience and identity cannot be reduced just to universities who are studying Afro-Latinidad from an academic perspective. Rather, Afro-Latinidad should be understood by the interdisciplinary nature with which it has consistently been displayed in and throughout the Americas by many people, over a variety of countries, social classes and religious affiliations, con una meta, como dice ChocQuibTown, de “Representarnos donde quiera.”[14]

For us to fully recognize, affirm, and value Afro-Latinidad as an identity, as a lived experience, and as an expression of the fullness of Latinidad, we also have to challenge our racialized theologies and challenge the use of antiquated language, theories and terminologies that all have one purpose, black erasure. Given its history, does mestizo appropriately convey the fullness of Latinidad or does it perpetuate racialized theologies that deny Black and Indigenous Latin@s? This is a necessary question to explore. A full appreciation of Blackness within Latinidad will not happen until we change how we talk about all people created in God’s image, and reaffirm what is written at the beginning of the Bible. That all people, Black people, Afro-Latin@s, are created in God’s image. “Then God said, ‘Let us make humankind in our likeness, to be like us.’ (Genesis 1:26a, TFET) and “Humankind was created as God’s reflection, in the divine image God created them…” (Genesis 1:27a, TFET).

Understanding the diversity of how Afro-Latinidad is expressed can be an initiation into a broader, richer personal recognition of how our identities connect us to various people across time. I don't know when or how old the next young person will be when they have that experience with Afro-Latinidad. I certainly hope that by then we have embraced a fuller definition of Latinidad, one that no longer places Afro-Latin@s on the margins, in liminal spaces, or claims that Afro-Latinidad is something new. I hope that when this happens we are able to understand the wholeness of Latinidad and center Blackness within it.

“Quisieron borrar nuestras huellas... ¡y hoy somos miles de miles!

Quisieron callar nuestras voces... ¡y hoy somos coros y ecos!

Quisieron invisibilizar nuestro rostro... ¡y hoy nuestra presencia más grande se yergue!

Quisieron arrancarnos de nuestra tierra... ¡y hoy somos raíces en el universo!

Porque no hay Lugar en el mundo -terrestre o etéreo- donde no existan huellas -profundas y perennes- dejadas por la mujer y el hombre negro.” - Lorena Torres Herrera[15]

Guesnerth Josué Perea is a teaching Pastor at Metro Hope Covenant Church, and one of the directors of the afrolatin@ forum, a non-profit that raises awareness of Latin@s of African descent in the United States. Josue holds a MA in Theology from Alliance Theological Seminary, a Continuing Education Certificate from Union Theological Seminary and a BA in Latin American History from CCNY. His research on Afro-Colombianidad has been part of various publications including Let Spirit Speak! Cultural Journeys through the African Diaspora and the Journal for Colombian Studies. Josué was named by the newspaper amNewYork as one of five Colombians "making a mark" in New York City.

[1] In Laurence E. Prescott, Without Hatreds or Fears: Jorge Artel and the Struggle for Black Literary Expression in Colombia (Detroit: Wayne State Univ. Press, 2000).

[2] http://www.afrolatinoforum.org/defining-afro-latin.html

[3] Román Miriam Jiménez and Juan Flores, “Introduction,” in The Afro-Latin@ Reader: History and Culture in the United States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 1-3.

[4] See this video for context: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HrtkPEBDUzM&t=1s

[5] Lachatanere, Diana. The Schomburg Papers. New York: University Publications of America, 1983.

[6] Schomburg, Arturo A. "The Negro Digs Up His Past". New York, 1925.

[7] Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

[8] In Román Miriam Jiménez, Juan Flores, and John Logan, “How Race Counts for Hispanic Americans,” in The Afro-Latin@ Reader: History and Culture in the United States (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 471-484.

[9] Román Miriam Jiménez and Juan Flores, “Introduction,” in The Afro-Latin@ Reader: History and Culture in the United States (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 2-3.

[10] “The earliest manifestations of Afro-Latin@ presence actually predate the very founding of the country and even the first English settlements. As reflected in Peter Wood’s title of the opening reading, the “earliest Africans in North America” were in fact Afro-Latin@s.” in The Afro-Latin@ Reader: History and Culture in the United States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), p. 4.

[11] For more info see Telles, Edward Eric. Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, Race, and Color in Latin America. Chapel Hill, NC, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

[12] “Latinos use sound and music to narrate a history of resistance and create a sense of belonging.” - Petra R. Rivera-Rideau et al., “Rethinking the Archive,” in Afro-Latin@s in Movement: Critical Approaches to Blackness and Transnationalism in the Americas (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan., 2016).

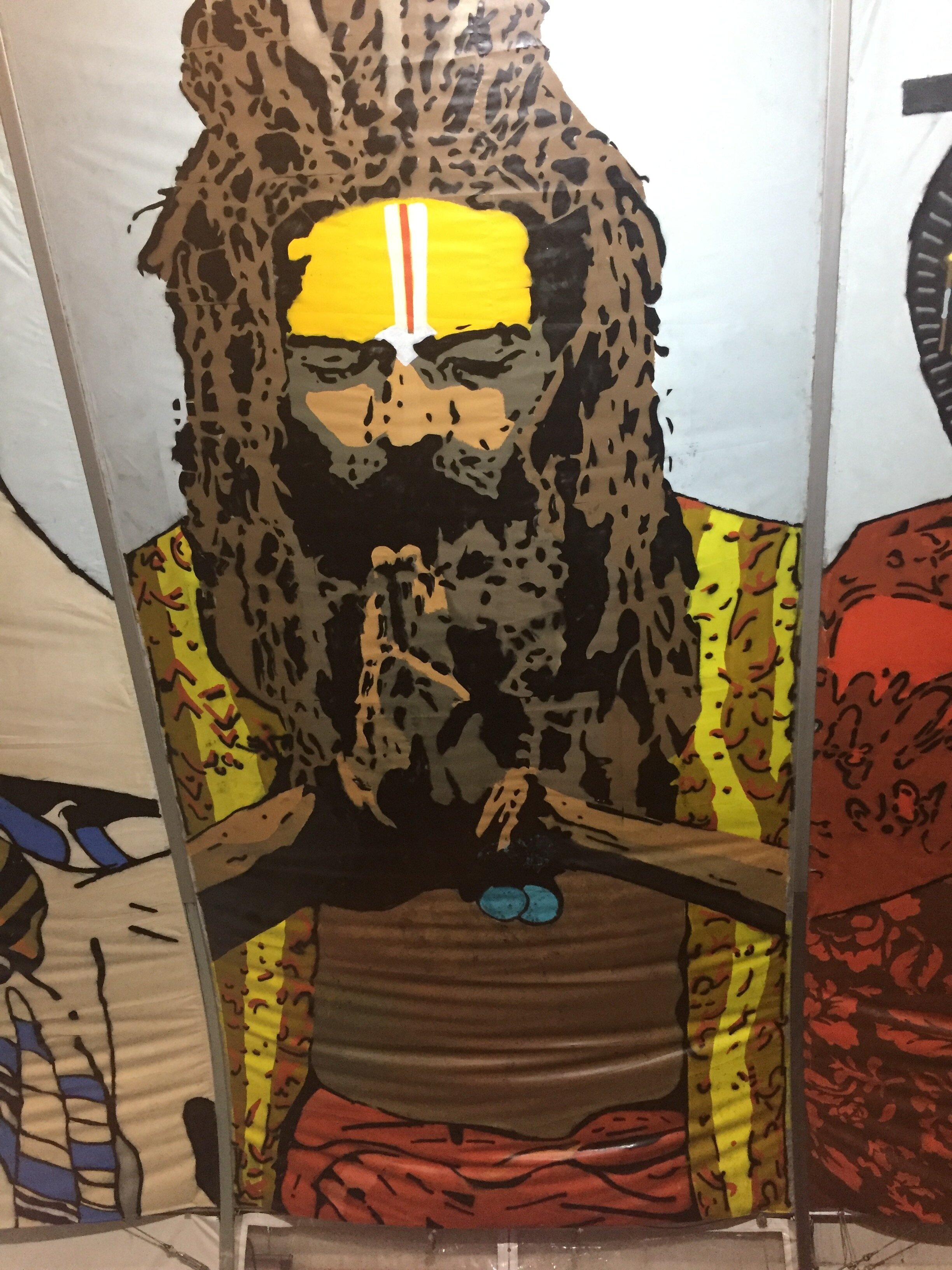

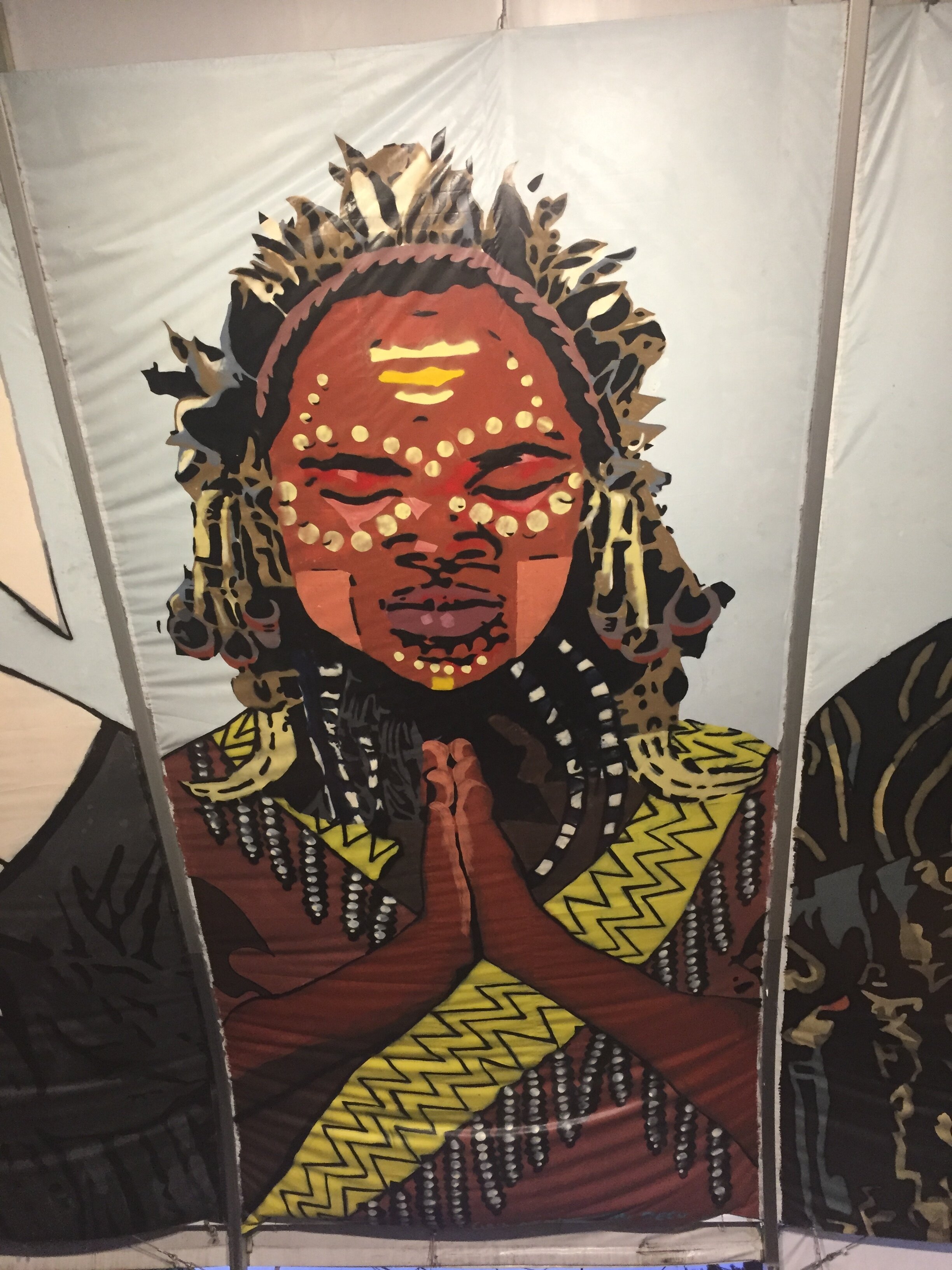

[13] Not to mention the many different visual artists that have kept Afro-Latinidad at the forefront such as Firelei Baez, Maria Magdalena Campos Pons and William Vilalongo just to name a few.

[14] Full video and song: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2wzqWhwt8zE

[15] Guiomar Cuesta Escobar, Alfredo Ocampo Zamorano, and Lorena Torres Herrera, “Siempre Presentes,” in ¡Negras Somos!: Antología De 21 Mujeres Poetas Afrocolombianas De La región pacífica (Bogotá́, Colombia: Apidama Ediciones, 2013).

![CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=937608 [5]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5dfd8beb22732d3b23495b1f/1577989241484-HKVUQ3DOPNPRI92VFOG4/Adams_onis_map.png)