Divided We Stand: Latina/o Students in White Institutions

This article was originally published on Shetheordinary, a blog created for those of us experiencing life in our diverse faith, culture, & identity.

“I don’t associate with that group of people,” he replied after I invited him to our El Puente club meeting, a student club designed for Latina/os enrolled in my Southern California alma mater. I was confused and offended. He shared that he was Mexican-American, had dark brown eyes, and brown hair with tan skin but resisted my invitation to meet other students like him. With a surprised face I looked at him and ended the conversation with a simple and quiet “ok.”

I could not verbalize my disbelief.

Here I was, a sophomore in college, attempting to connect with someone who looked like me but shared a completely different view of our cultural identity. I never experienced this before. Being born and raised in Los Angeles exposed me to a majority of Latina/os friends who identified with their parents’ culture. We grew up bilingual and well aware of our raices. There was no question in proclaiming ourselves as proud Brown children.

After my brief conversation with this young Latino, I was left sitting alone at the table in a college cafeteria. My coraje (anger) crept in. With him gone, my delayed reaction came in full force.

“Forget you!” I thought to myself, “You can’t even see your nopal en la frente, Pocho!”

In our small Christian college campus there were two sub-groups of Latina/o students. Those who proudly associated themselves as Brown and those who disassociated themselves from their Latina/o roots. My dad would call these people, ‘Pochos.’

As a Mexican-American, if you did not know or speak the Spanish language, and rarely identified with your cultural roots, you were called a ‘Pocho.’ This was an insult and a statement indicating that your latinidad has been revoked by your unworthiness to prove it. You were seen as a white-washed Latina/o, uncultured and assimilated.

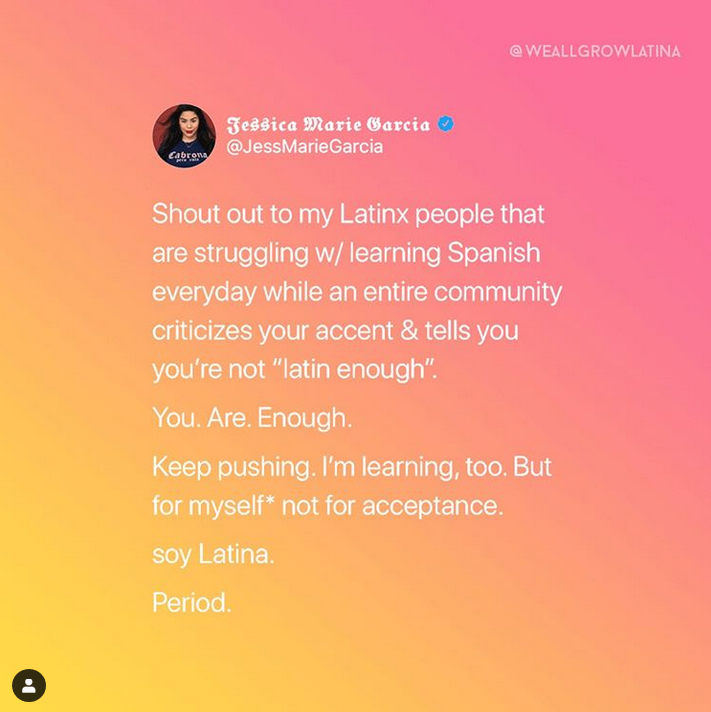

My interaction with this young Latino was not the only one that angered me during my time as a student. Many other Latina/o classmates created a dichotomy of us versus them within our own Brown students on campus. This created a deeper scar on all of our cultural identities from wherever we stood on the spectrum of identifying with our heritage. I could not help but wonder why these young men and women were so ashamed of their identity - ashamed of the language of their ancestors? Eventually I wondered why they were even ashamed of associating with a person like myself, someone who fully identified with her latinidad.

In Brown Church: Five Centuries of Latina/o Social Justice, Theology, and Identity, author Robert Chao Romero quotes Laura Gomez on the following: “As Brown-somewhere between white and black-a select minority among us has always had the option to slip into whiteness and forget about the rest.”[1] I can’t help but think this is what happens with some of us struggling to identify with our cultural identity.

We slip into our whiteness when we choose to disown our Brown brothers and sisters. We repress who we are to be accepted and seen in the same value as our white counterparts. This comes at the cost of cutting our raices and cultural ties with one another as Brown people.

In her article, “El Español in the US: Memoria and Resistance”, Itzel Reyes shares a little more behind this decision to repress and assimilate. In her words, some of our parents “stopped teaching Spanish to our children as a protective strategy, as a survival mechanism disguised as choice. We sacrificed our descendants’ ability to speak with their own family in service of racist ideologies. We forcefully traded our ability to communicate with our familias in exchange for a little bit of acceptance from a system that does not recognize us as image-carriers.”

For some of us, our assimilation has been an act of survival passed down from generation after generation in order to survive in White America.

We repress, disassociate, and look at our proud Brown people with little to no connection. Yet, no matter how much some of us try to remove our ‘Brown’ attributes, language, and heritage, this will never make us immune to the discrimination and ignorance we face in this country because our society has been embedded with historically racist systems that still haunt us today.

I look back and cannot help but feel a nudge from the Holy Spirit to reconcile with this young Latino in the cafeteria. At the time, I disliked him for thinking he was better than me. Yet, my reaction to his comment placed me in the same path as him after calling him a Pocho (sorry God). He pushed proud and expressive Latina/os away from him and I only drew this line farther back. I thought I had the right to exclude him from our heritage, one that has been scrutinized and judged by a toxic racist ideology only learned and adopted. We traded our native tongue for a language of self-hate. In consequence of this complex disconnect, you see my example of losing respect for him thinking that latinidad was something I could measure and hold to a standard. I failed to understand the history of this country that stripped him, his family, and many others from being their authentic selves.

Institutions and systems built on racism will pin us against each other leading us to cut cultural ties from one another. We cannot give in to this division because in the end we are in the same fight to be seen and heard for who we are.

As God’s people, we must make room at the table even for those who are not there yet to fully embrace their latinidad and culture. We make room for those still struggling to fully embrace the beauty in the color of their skin, their different shades of brown, and the beautiful language(s) of our ancestors. As Latina/os, building community is a core value among us and assimilating and rejecting one another is not how we will move forward in this country. We will progress only by meeting each other where we are, through the full embrace and grace led by the God who draws us closer to one another.

From time and time again we will see those of us who are approaching the cafeteria table blindfolded with the red, white and blue bandanna of racism. They will come rejecting you and themselves, rooted out of a generational fear and burden passed down from long ago. Give grace and leave a seat open at the table for them. They are going to need a gentle uncovering in due time to see life in the light of Christ.

In the book of John chapter nine, Jesus heals the man born blind to show those who think they see that they are truly blind. Verse three of chapter nine states that neither did this man nor his parents sin for him to be born blind. Instead, this circumstance and moment is presented for the Messiah to display his work as the one who recovers sight to the blind.

In his healing power, Christ leads us to see one another for who we truly are. Through his grace and power, Jesus uncovers our eyes to see the goodness and beauty in our Brown face and with one another.

We no longer remain blind to one another and our God-given color, instead we see each other in the light of Christ with kindness and full acceptance. May we continue this restorative work and find healing, reconciliation and connection once again.

About Heidi Lepe

Heidi Lepe is a West Los Angeles Latina blogger and creator of Shetheordinary, an online platform for individuals experiencing life at the intersections of faith, culture and identity. As a daughter of Mexican/Honduran immigrant parents, she completed her dual Bachelor’s degree in Psychology and Sociology from Vanguard University in 2015 where her love for theology and culture began. She loves reading/writing, traveling, and eating a traditional Central American breakfast at any time of day. You can read more of her writings at www.shetheordinary.com and follow her upcoming projects on Instagram/Facebook @shetheordinary.

Footnote

[1] Robert Chao Romero, Brown Church: Five Centuries of Latina/o Social Justice, Theology, and Identity, n.d.

![CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=937608 [5]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5dfd8beb22732d3b23495b1f/1577989241484-HKVUQ3DOPNPRI92VFOG4/Adams_onis_map.png)