This article is from a forthcoming series in the Moody Center magazine. To learn more about the magazine and Moody Center, subscribe to their newsletter.

When we attend to the cries of suffering people, we reflect God—not Pharaoh.

Buckling under the weight of generational systematic subjugation, Israel cried out to God and God listened. “And the people of Israel groaned under their bondage, and cried out for help, and their cry under bondage came up to God. And God heard their groaning, and God remembered his covenant…And God saw the people of Israel, and God knew their condition” (Ex. 2:23-25). When God called Moses, God emphasized hearing Israel’s cries: “I have seen the affliction of my people who are in Egypt, and have heard their cry because of their taskmasters; I know their sufferings, and I have come down to deliver them out of the hand of the Egyptians…And now, behold, the cry of the people of Israel has come to me, and I have seen the oppression with which the Egyptians oppress them. Come, I will send you” (Ex. 3:9-10). Exodus contrasts this attentive divine listening to Pharaoh’s callous indifference. When God brings Israel’s cries to Pharaoh through Moses, Pharaoh increases Israel’s labors and suffering. Israel responds by crying out to Pharaoh, not God. But Pharaoh again entrenches in injustice (Ex. 5:15-19).

In the New Testament, Jesus and the Apostles also stress the paramount importance of listening to the cries of suffering, subjugated people. Consider, for example, Jesus’s parables of the Good Samaritan (Lk 10) or the rich man and Lazarus (Lk. 16). Or recall James’s declaration that “religion that is pure and undefiled before God the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world” (Jm. 1:27). Godliness requires listening to and caring for suffering people in their affliction. Worldly defilement does not; it fosters entrenchment in unjust sins of commission and omission—like Pharaoh’s worsening Israel’s plight and ignoring their cries.

Impediments to Godly Hearing when We Read

Godly attentive listening follows from love. In Exodus, God’s love for the people of Israel and their covenant ancestors motivates God to liberate them from physical, political, and spiritual bondage. Jesus’s parables and James’s declaration about pure religion reflect the biblical vision of how neighbor-love motivates godlike attentive listening. Sometimes this love-infused listening is literal; we hear the cries of those suffering around us. Other times this listening is metaphorical; when we read about the suffering of others, we “hear” them through the page. Therefore, when we hear people’s suffering through reading, we imitate God.

But, as with physical hearing, impediments often obscure our ability to hear suffering people’s cries when we read. One impediment is applying the wrong kind of reading practice to a text. C.S. Lewis, for example, distinguishes between reading practices that use a text from those that receive a text. When we use a text, we treat it as a means to information or distraction. This is fine when reading a menu or a joke; it is inappropriate when reading a love letter, petition, or religious text. These works require we read to receive—that we humbly approach the texts with a willingness to let them confront and change us.

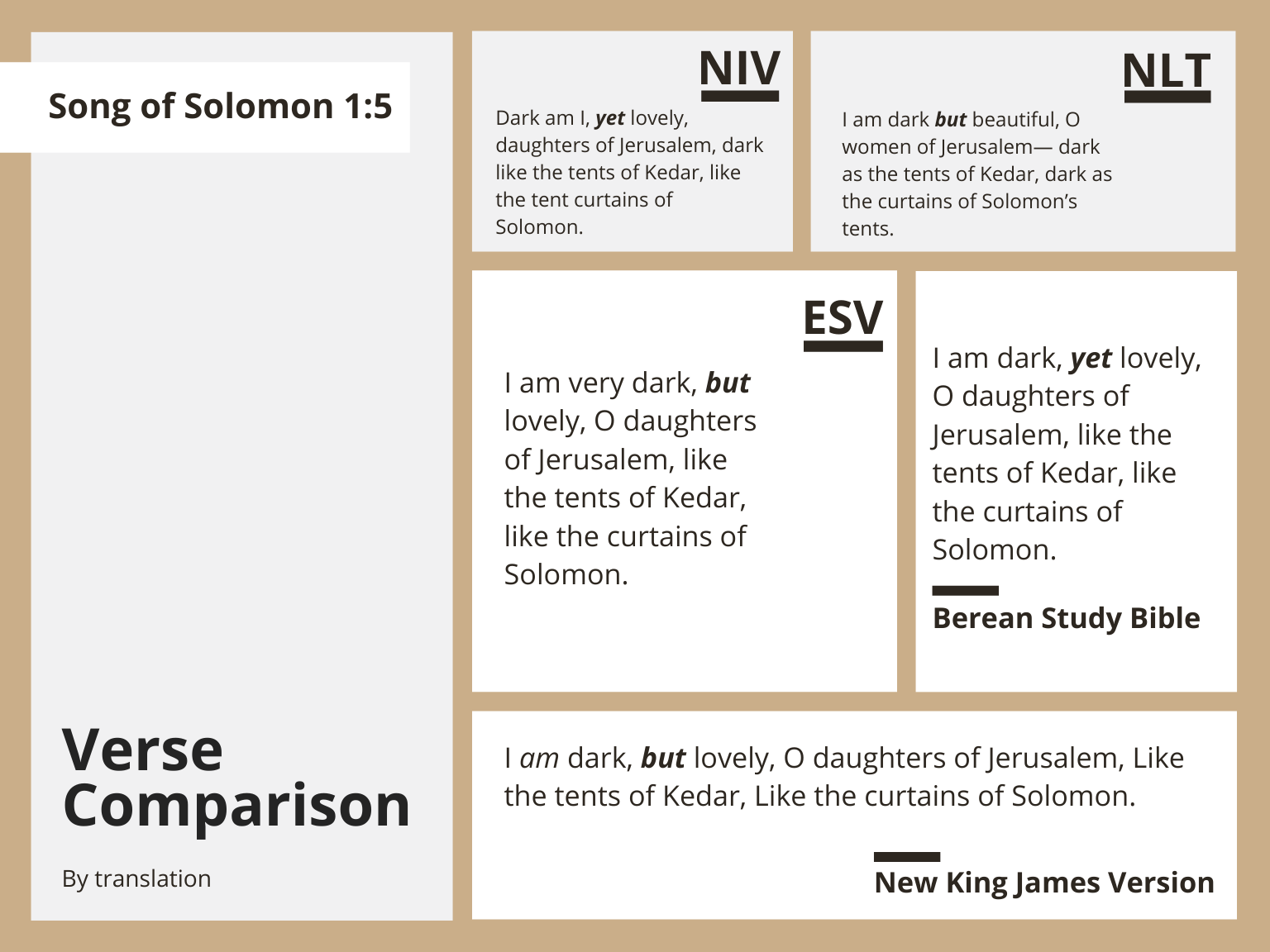

C.S. Lewis notes another obstacle to hearing suffering through a text: We are socially located readers and thinkers socialized to hear and see some things and not others. Lewis writes: “Every age has its own outlook. It is specially good at seeing [and hearing] certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes.” James Cone makes a similar point. “There is no place we can stand that will remove us from the limitations of history and thus enable us to tell the whole truth without the risk of ideological distortion.” To minimize or avoid these social and ideological limitations, Cone instructs us to “listen to others outside of our own time and situation.” Likewise, Lewis encourages us to read “the old books,” because they help us recognize and adjust for “the characteristic mistakes of our own period.”

Sadly, Lewis’s and Cone’s proposals cannot guarantee that we hear the suffering voices around us when we read. Sometimes the old books are silent about or obscure our current challenges. The Bible says nothing about the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act or its continued impacts on China and the United States. Moreover, many older histories lie about the United States.

Reflecting on the rise of intentionally false narratives about U.S. Reconstruction (1865–1877), W.E.B. Du Bois writes:

I stand at the end of [ writing Black Reconstruction in America], literally aghast at what American historians have done to this field…[these histories are] useless as science and misleading as ethics… [and they show] that with sufficient general agreement and determination among the dominant classes, the truth of history may be utterly distorted and contradicted and changed to any convenient fairy tale that the master of men wish.

What Du Bois chastised in Reconstruction histories, Leon Litwick, president of the Organization of American Historians, applied generally to U.S. historians: “No group of scholars was more deeply implicated in the miseducation of American youth and did more to shape the thinking of Americans about race and blacks than historians.” Most in the U.S. continue to inherit these false histories and their accompanying ideologies. We suffer these injustices. Moreover, receiving these unjust histories obstructs our abilities to hear the stories of how our neighbors and we suffer from white supremacy. This impediment is especially dangerous, for as Cone observed, “When people can no longer listen to other people’s stories, they become enclosed within their own social context, treating their distorted visions of reality as the whole truth.”

Hearing Our CRT Neighbors

Enter critical race theorists. Scholars such as Derrick Bell, Richard Delgado, Robert A. Williams, Jr. (Lumbee), Gary Peller, Mari Matsuda, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Imani Perry, and Laura E. Gómez write essays aimed at helping us see how U.S. law and legal institutions have maintained and perpetuated white supremacy and hear the cries of non-white and white communities and individuals suffering from these racist evils. CRT scholars do not claim to stand-in for these communities or individuals. Like Ada María Isasi-Díaz, they would say, “Though I do not speak for them, I speak with them and on behalf of them.”

As they speak, CRT scholars remind us of legal decisions like these:

Power, war, conquest, give rights, which, after possess, are conceded by the world, and which can never be controverted by those on whom they descended. –Chief Justice John Marshall, Worcester v. Georgia (1832) [This is still official U.S. Federal Indian law]

In the opinion of the court, the legislation and histories of the times, and the language used in the Declaration of Independence, show, that neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument. –Chief Justice Roger Taney, Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857)

All people under U.S. jurisdiction have the same right to make contracts and pursue business opportunities “as is enjoyed by white citizens.”—1866 Civil Rights Act [This is still official U.S. law]

There is a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the US...I allude to the Chinese race.—Justice John Harlan’s dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) referencing the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act

Most of us are unfamiliar with these quotations and the painful, subjugating roles they have played in shaping communities and individuals. We do well, then, to engage CRT texts, working to receive rather than use them, in order to hear these truths and the cries they amplify. These practices will help us imitate God, not Pharaoh. They will help us heal from injustice. And they will help us care for Jesus and our neighbors (Mt. 25).

About Nathan Cartagena

A son of the US South (Mom) and Puerto Rico (Dad), Dr. Nathan Luis Cartagena is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Wheaton College (IL), where he teaches courses on race, justice, and political philosophy, and is a fellow in The Wheaton Center for Early Christian Studies. He serves as the faculty advisor for Unidad Cristiana, a student group working to enhance Christian unity and celebrate Latina/o cultures, a scholar-in-residence for World Outspoken, and a co-host for the forthcoming podcast From the Underside. He’s also writing a book on Critical Race Theory with IVP Academic. For more about hermano Nathan, visit his website.

Articles like this one are made possible by the support of readers like you. Donate today and help us continue to produce resources for the mestizo church.