Editors Note: Throughout this essay, “black” refers to the color while “Black” refers to the historic racialized community.

“Our theology never comes from a blank space.””

“The reclamation of racial beauty in the sixties stirred these thoughts, made me think about the necessity for the claim…Why did [Black beauty] need public articulation to exist?””

Christians are people of the Book, the library of sacred texts that we call the Bible. The Old and New Testaments contain the inspired word of God. They are, as the apostle Paul writes, God-breathed (2 Timothy 3:16). And so, they are “useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting, and training in righteousness.”

Yet none of these inspired texts was God-breathed through a modern language. Each was originally etched in Hebrew, Greek, or Aramaic—not Mandarin, Arabic, Portuguese, or Spanish. Unless you read the former ancient languages, you encounter the sacred page through the veil of translation.

But even translators of the original biblical languages encounter scripture through a veil. What New Testament scholar C. René Padilla writes about interpreters applies to translators: “Interpreters do not live in a vacuum. They live in concrete historical situations, in particular cultures. From their cultures they derive not only their language but also patterns of thought and conduct, methods of learning, emotional reactions, values, interests and goals.” Translators are socially situated readers and interpreters. Their contexts and commitments—to say nothing of character—infuse their handling of Scripture. As Padilla argues, “whenever interpreters approach a particular biblical text they can do so only from their own perspective. This gives rise to a complex, dynamic two-way interpretive process depicted as a ‘hermeneutical circle’, in which interpreters and text are mutually engaged.”

Recognizing these dynamics, New Testament scholar Esau McCaulley calls for Bible publishers to hire multi-racialized and multi-ethnic translation teams. McCaulley writes:

I’ve discovered that people of color and women have rarely led or participated in Bible translation. On one hand, this doesn’t trouble me much. It is hard to mess up the story of the Exodus, distort the message of the prophets or dismantle the story of Jesus. It is all there in every English translation.

On the other, I believe it matters who translates the Bible, and that more diverse translation committees could inspire fresh confidence among Christians of color….

The insight, experience and skills of female scholars might open our eyes to nuances that a committee of all men might miss. Christians for whom English is a second language might highlight ways in which our word choice is unclear. Similarly, [B]lack Christians may call to mind neglected aspects of the text.

McCaulley supports his call for diverse translation teams by considering English translations of Exodus 12:38, beginning with the King James Version. When Israel leaves Egypt, “a mixed multitude went up also with them” (KJV). McCaulley notes that “Nearly all scholars agree that the original Hebrew meant to highlight that an ethnically diverse group of people left Egypt with the Jewish people. This group could have included Egyptians and other ethnic groups, such as the Cushites.” So, whereas “The translation ‘mixed multitude’ isn’t necessarily wrong,” McCaulley argues, “It simply does not communicate the power of this simple verse in a way that would be understood by those reading today. If I were translating the passage, I would say that ‘an ethnically diverse crowd’ went up out of Egypt.”

McCaulley’s alternative translation is a mild corrective of the KJV. He does not deem it wrong nor unfit for its time. Instead, McCaulley argues that it and modern English translations that speak of a “mixed multitude” leaving Egypt (e.g., ESV) neglect linguistic frequencies that carry important conceptual and contextual insights for today’s English readers.

I affirm McCaulley’s call for racial, ethnic, and gender diversity in translation teams and his proposed alternative translation of Exodus 12. I’d like to extend both by arguing that anti-Black racist ideas have crept into English Bible translations. To see what I mean, let’s turn our attention to the King James’s translation of a verse in Song of Solomon.

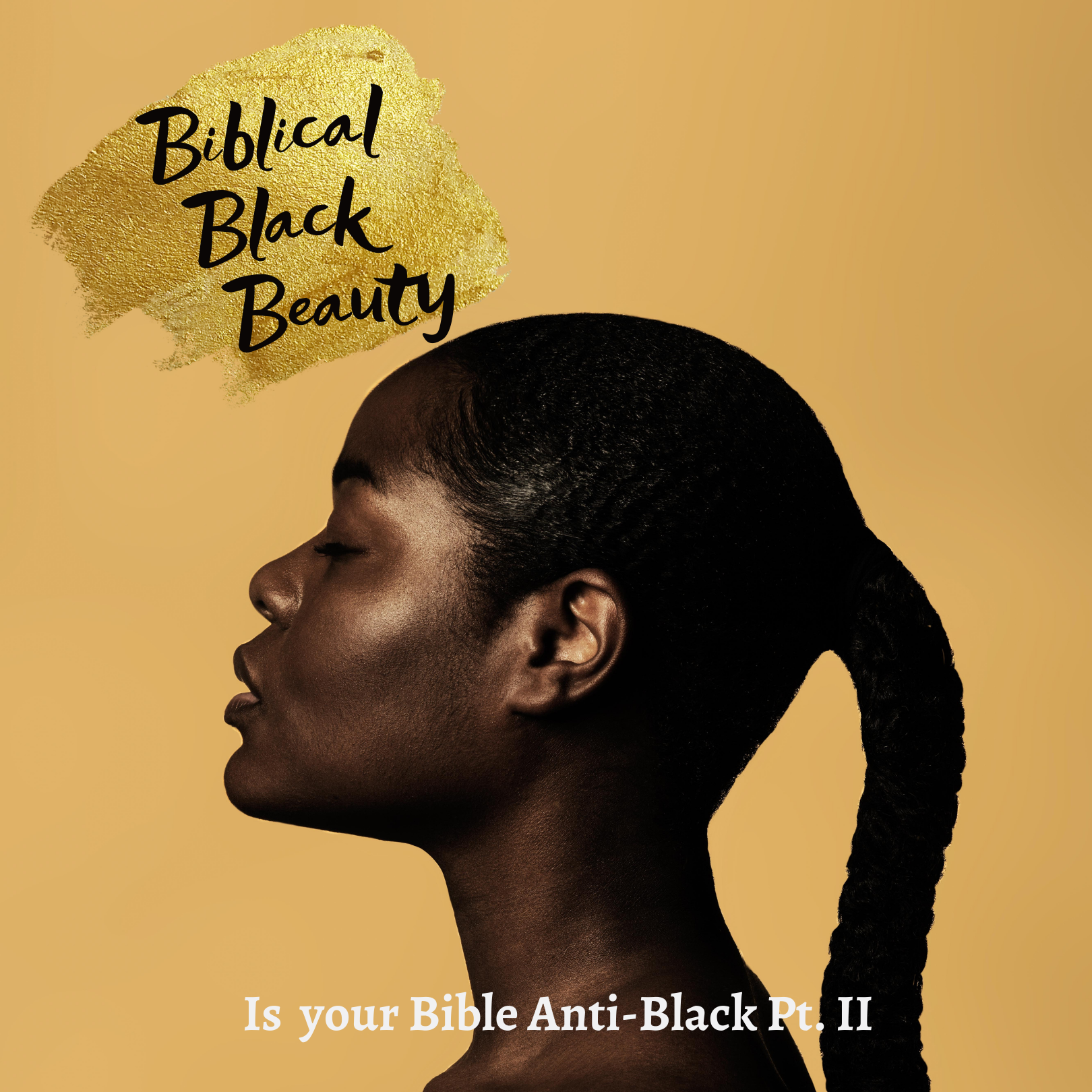

Is Blackness Beautiful?

Song of Solomon begins on an exuberant note. After noting that it is the song of songs and belongs to Solomon, the song’s primary female figure professes her enthusiasm to be with her beloved.

Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth: for thy love is better than wine.

Because of the savour of thy good ointments thy name is as ointment poured forth, therefore do the virgins love thee.

Draw me, we will run after thee: the king hath brought me into his chambers…(vv. 2-4)

A supportive, enthusiastic chorus enters the text to celebrate this highly anticipated joining. “We will be glad and rejoice in thee, we will remember thy love more than wine: the upright love thee” (v. 4). All is right. All rejoice.

The text turns to the female’s first self-description. Here’s the original Hebrew, reading right to left:

שְׁחוֹרָ֤ה אֲנִי֙ וְֽנָאוָ֔ה בְּנ֖וֹת יְרוּשָׁלִָ֑ם כְּאָהֳלֵ֣י קֵדָ֔רכִּירִיע֖וֹת

Here’s how KJV reads: “I am black, but comely [beautiful], O ye daughters of Jerusalem, as the tents of Kedar, as the curtains of Solomon” (v. 5) Those who read Hebrew will recognize that the KJV has failed its readers.

The failure comes in verse five’s opening. The KJV’s translation team renders “שְׁחוֹרָ֤ה אֲנִי֙ וְֽנָאוָ֔ה” as “I am black, but comely [beautiful].” But as Old Testament scholar Wilda Gafney observes, this translation choice is grammatically impossible. The conjunction וְֽ at the start of וְֽנָאוָ֔ה means “and”—not “but.” Moreover, as Gafney argues, because there isn’t a “but” in Hebrew, authors writing in Hebrew must compile “a bunch of stuff to make a disjunction”; they can’t simply use a conjunction that means “and.”

Gafney realized these linguistic truths as a child. From a young age, she loved learning languages and desired a more direct relationship with the biblical text. As she compared the Hebrew and KJV, she saw “it was wrong in the King James Bible that I grew up with, where it said, ‘I am black but beautiful.’” This sparked a second realization:

The people translating [that passage] could not see blackness as beautiful, and so their whole identity [as self-identified white men] went into that one conjunction saying, ‘in spite of being Black, she’s all right.’ But that is not what the text said. And so that was the first place where I understood that people make choices when they translate [the Bible], and those choices affect what we hear [from the text].

McCaulley’s alternative translation of Exodus 12:38 mildly corrects the KJV’s. Gafney’s alternative translation of Song of Solomon 1:5 is a damning corrective of the KJV. It highlights that the KJV’s rendering is wrong—and layers anti-Black racist ideas onto the biblical page.

The KJV’s Racial Context

Gafney claims that the KJV’s translation team injected their anti-Black sentiments into the KJV. For many, this claim is jarring. Congregations that use the KJV rarely discuss the translation’s racial context (or content). The same holds for academic treatments of the text. David Lyle Jeffery’s, Alister McGrath’s, and David Norton’s books on the KJV say nothing about the text’s racialized context (or content). None have an index entry on “race,” “whiteness,” or “white supremacy”—let alone a sustained discussion about the anti-Black translation of Song of Solomon 1:5. Though from different parts of the globe—Canada, Ireland, and England, respectively—none of these racialized white authors ensured their books addressed the KJV’s racial dimensions. What Gafney noticed as a youth, they overlook in their mature academic writing.

Given these ecclesiastical and scholarly omissions, a word about the KJV’s racial context is in order. Let us consider two aspects of this context: international anti-Blackness and anti-Blackness in contemporary English literature and theatre.

Starting in the fifteenth century, a racial scale that prioritized “whiteness” informed European imperialism. The first recorded slave auction makes this clear. Reflecting on the year 1444, Portugal’s royal chronicler Gomes Eanes de Azurara writes:

[On] the next day, which was the 8th of the month of August, very early in the morning, by reason of the heat, the seamen began to make ready their boats, and to take out those captives, and carry them on shore, as they were commanded. And these, placed all together in that field, were a marvelous sight; for amongst them were some white enough, fair to look upon, and well proportioned; others were less white like mulattoes; others again were as black as Ethiops [Ethiopians], and so ugly, both in features and in body, as almost to appear (to those who saw them) the images of a lower hemisphere.

All depicted are slaves; not all are equal. Some are “white,” and therefore “fair to look upon, and well proportioned.” Others are “less white like mulattoes,” and, apparently, deserve little discussion. Others still are “black,” and hence “ugly”—as if they had come from Hell itself. Here is a scale that advances white supremacy and anti-Blackness.

European colonizers repackaged and disseminated Azurara’s scale as they constructed pigmentocracies—governments for and by those deemed “white.” Historian C.R. Boxer notes that, although Portugal and Spain respectively granted mesticos and mestizos a positive colonial status, “both Iberian empires remained essentially a ‘pigmentocracy’ . . . based on the conviction of white racial, moral, and intellectual superiority—just as did their Dutch, English, and French successors.” Race scholar and sociologist Howard Winant similarly observes that these European colonial powers believed they were “the whites, the masters, the true Christians.” And historian Winthrop Jordan succinctly captures this trend among the British, highlighting that, during the seventeenth century, English colonists treated “Christian, free, English, and white” as metonyms. For them, each word was equivalent.

The racialized language Jordan details has antecedents in English literature that’s contemporary with the KJV, which was published in 1611. In 1578, the widely read English travel writer George Best offered a damning account of “the Ethiopians blacknesse.” While discussing his Artic voyage, Best argued that, because Ham had sex on the Ark, God cursed Ham and his descendants to be “so blacke and loathsome that it might remain a spectacle of disobedience to all the worlde.” Thus, Best championed a racialized curse theory which linked Blackness to ugliness and hypersexuality. Similar anti-Black ideas populate William Shakespeare’s plays.

The first Black character in Shakespeare’s plays is Aaron, the evil, deceptive, hypersexual, murderous Moor in Titus Andronicus (1594). The most famous Black character in Shakespeare’s plays is also a Moor: Othello (1604). Iago, Othello’s ensign, despises the Black Othello for marrying the White Desdemona. “For that I do suspect the lusty Moor/Hath leaped into my seat,” Iago claims. And while talking to Desdemona’s father, Iago says Othello is “an old black ram/…tupping your white ewe.” Iago later tricks Othello into believing that Desdemona has betrayed him. Before Othello kills Desdemona, he cries, “Her name that was fresh/as Dian’s visage, is now begrim’d and black/As mine own face.” After Othello learns that he unjustly killed his wife, Emilia, Desdemona’s maidservant, declares: “O! the more angel she. And you the blacker devil.” The Tempest’s (1611) Caliban also recapitulates the conceptual linking of Blackness and Satan that filled European theatre. Caliban is the bastard child of an African witch from a “vile race” and a demon. Caliban is also hypersexual.

Other English playwriters also employed anti-Black ideas and images. Ben Jonson’s The Masque of Blackness (1605) is especially important for our discussion. Commissioned by King James I, Jonson’s play was the most expensive production made in London. Premiering in the luxurious Whitehall Palace, the play is the story of twelve ugly African princesses of the river god Niger. The princesses learn that they can be “made beautiful” if they go to “Britannia,” for there the sun “beams shine day and night, and are of force/ To blanch [make white] an Æthiop, and revive a corpse.” White women, including Queen Anne, played the Black princesses. How? They used blackface.

White supremacy and anti-Blackness occupied a privileged place in European imperialism and English literature and theatre. Shakespeare and Jonson composed and presented plays that drew upon, shaped, and perpetuated anti-Black and pro-White English sentiments. These international and cultural realities were pillars of the KJV’s racial context.

Returning to the Song of Solomon

The KJV’s anti-Black translation of Song of Solomon 1:5 reflected its cultural context. It also shaped other cultures around the globe and across the centuries. The U.S. is a case in point. As historian Mark Noll argues, the KJV was the U.S.’s national book in the nineteenth century. Biblical language and allusions filled U.S. public discourse, and “the vast majority of public Bible references came from a single translation”—the KJV. It was this translation that filled debates about the U.S.’s slavocracy and global racialized chattel slavery. Moreover, it was this translation that became a staple in African American congregations and homes. Recall that Wilda Gafney grew up on the KJV. So did Esau McCaulley.

I grew up in a [B]lack Baptist church that revered the King James Version (KJV). Whenever it was read aloud, the congregation rose to its feet. But the KJV was more than a book read on Sunday. It shaped the culture of Southern black Christianity. Its thees and thous permeated our parents’ extemporaneous prayers. It marked the rhetoric of our most powerful preachers.

McCaulley argues that his experiences are common for Black Christians in the North or South. “If Flannery O’Connor can say that the South is Christ-haunted, then we can say that [B]lack Christianity is haunted by King James.” We hear this haunting hum in James Baldwin’s and Toni Morrison’s books and essays.

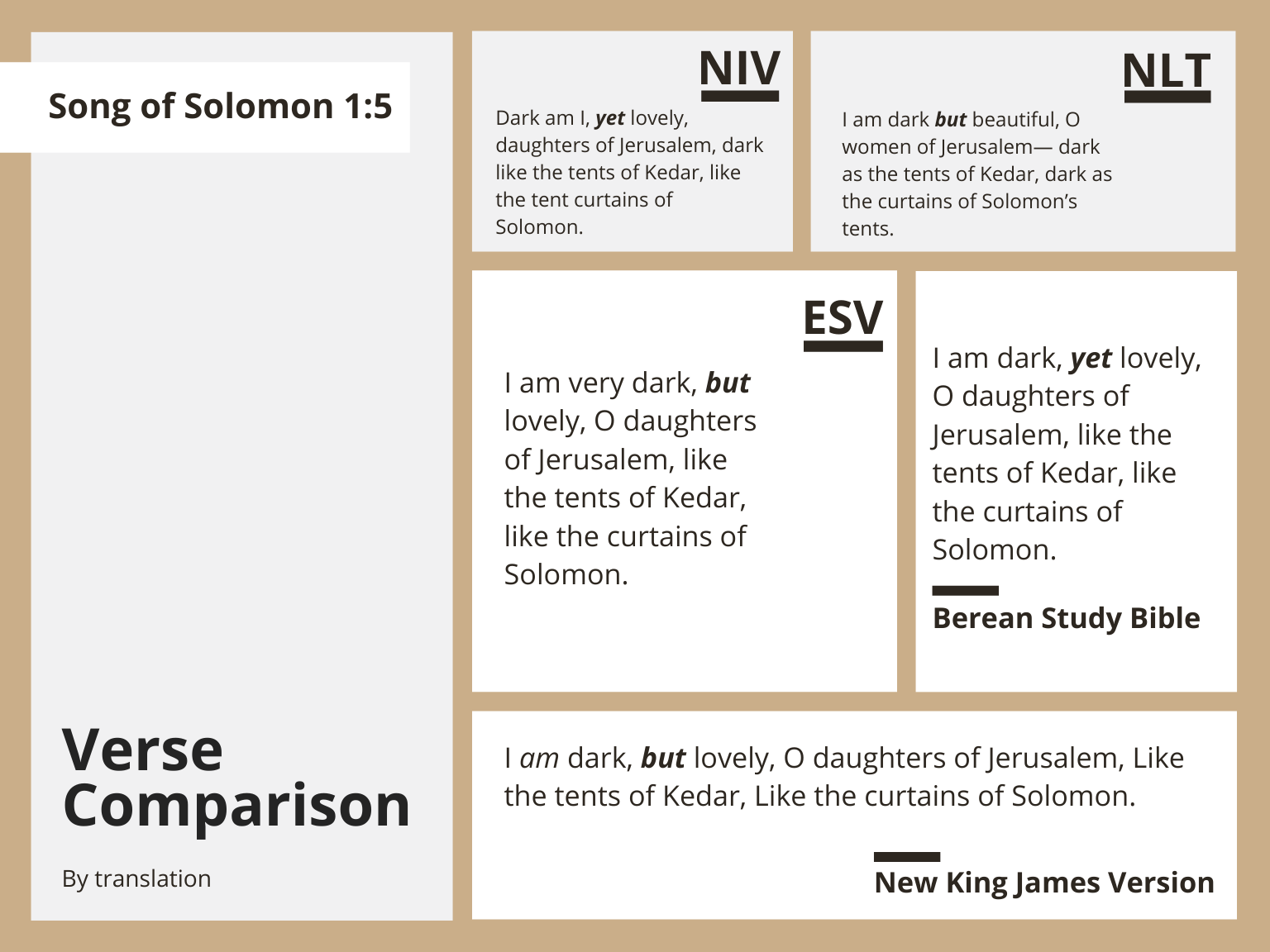

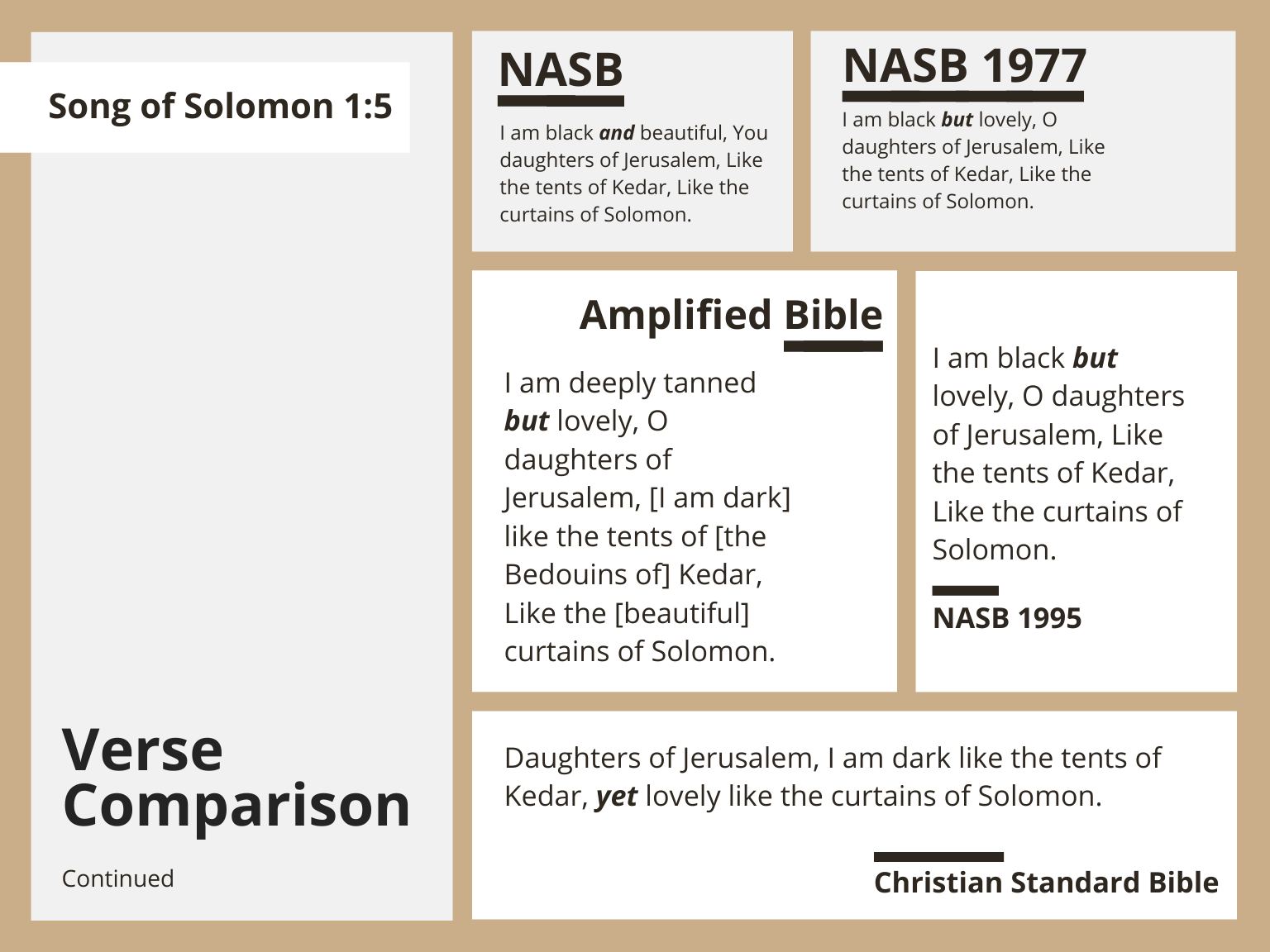

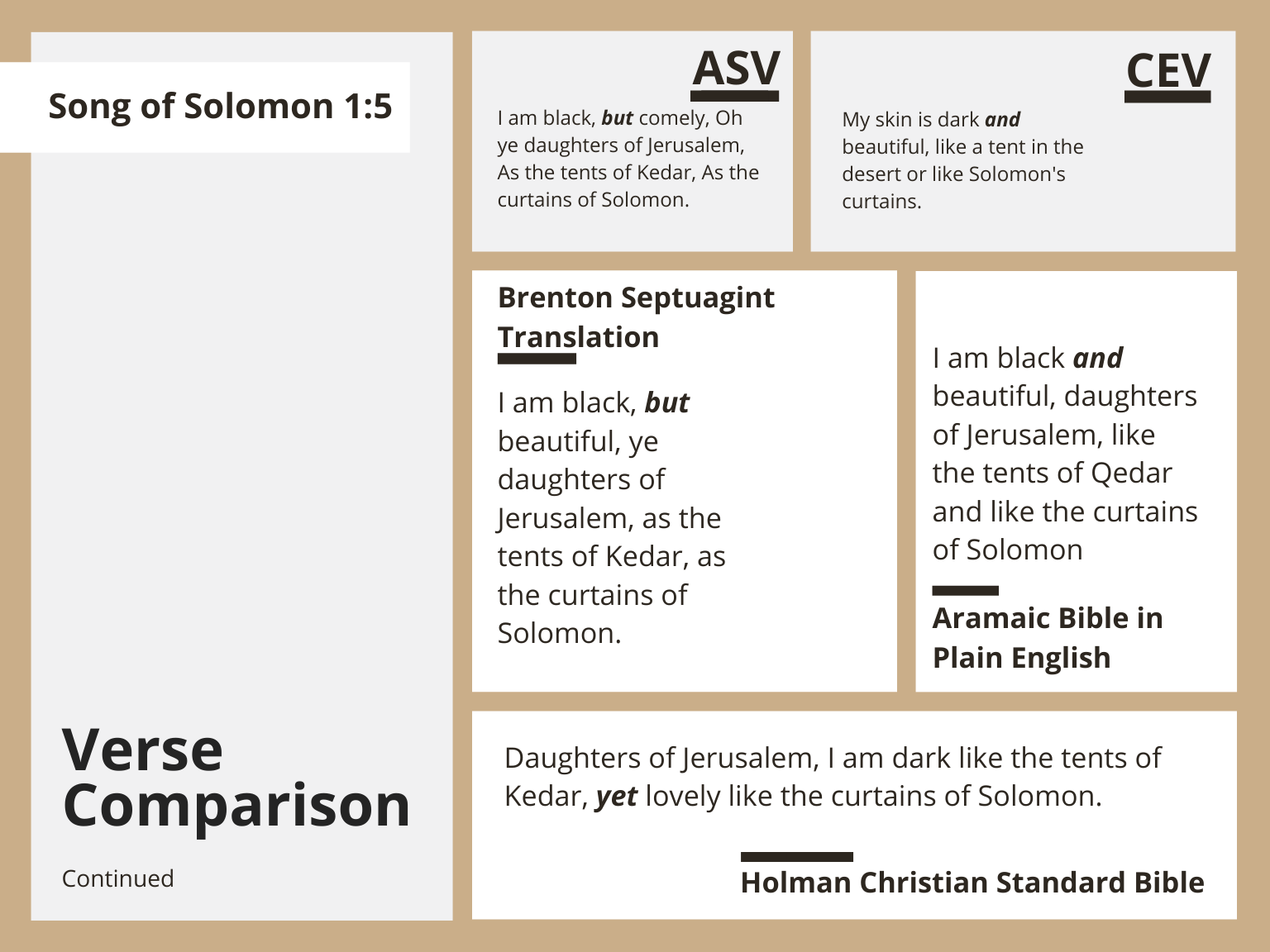

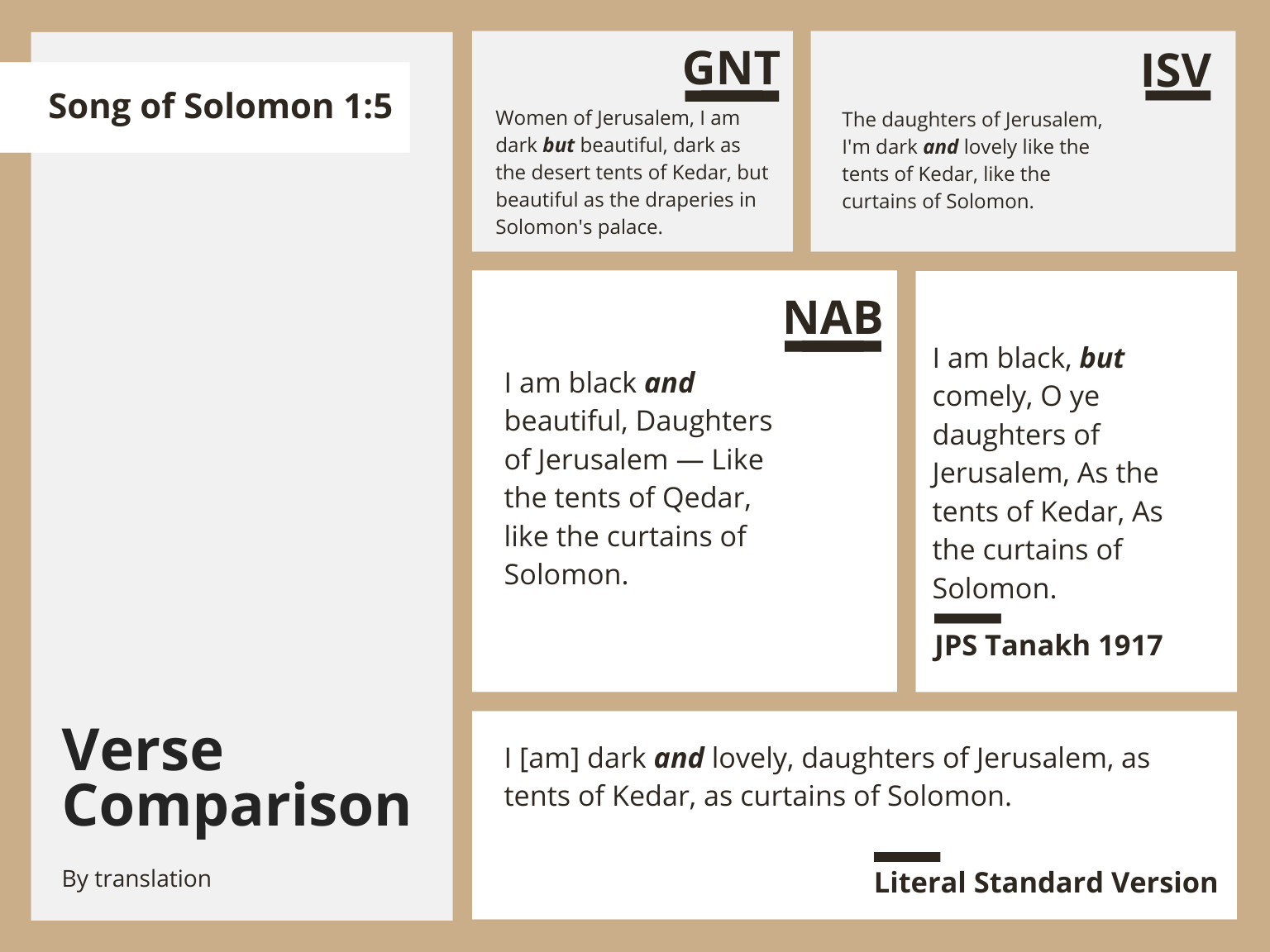

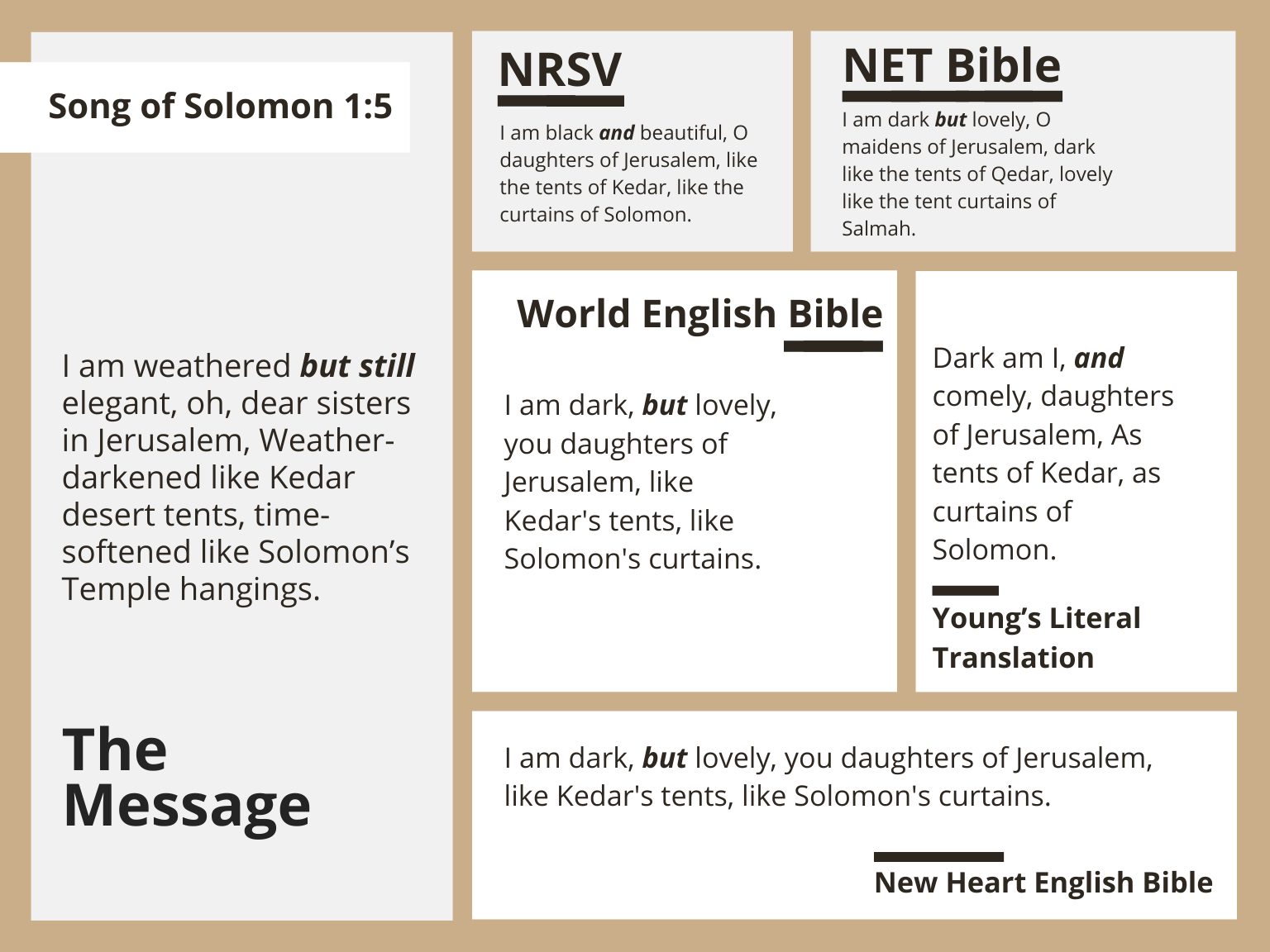

The KJV may also haunt modern English Bible translations of Song of Solomon 1:5. Consider these twenty-six translations (emphasis added):

Like the KJV, fourteen of the twenty-six versions offer a grammatically impossible translation with “but.” Four others offer a similarly impossible translation of “yet.” Only eight versions correctly translate the text’s “and.” Consequently, eighteen of these modern English translations—an arresting sixty-nine percent—give readers a wrong translation that perpetuates an anti-Black idea about beauty that the original Hebrew rejects. Thus sayeth the Lord, indeed.

Black is Beautiful

Biblical translations matter. They help or hinder our ability to encounter God and creation. They rebuff or retrench idolatry. They foster or fizzle love of self and neighbor. Song of Solomon teaches that black is beautiful. The Song’s primary female figure is beautiful and black. There is no contrasting conjunction here. Rightly encountering God and creation require seeing and feeling this truth. So does rebuffing the historic idolatry of whiteness. So does Black self-love and love of our Black neighbors. A diverse translation team populated by members with the lived experiences, communal ties, and interpretive skill of a Wilda Gafney would empower English Bible readers to experience and celebrate these God-breathed truths.

About Dr. Nathan Luis Cartagena

A son of the US South (Mom) and Puerto Rico (Dad), Dr. Cartagena is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Wheaton College (IL), where he teaches courses on race, justice, and political philosophy, and is a fellow in The Wheaton Center for Early Christian Studies. He serves as the faculty advisor for Unidad Cristiana, a student group working to enhance Christian unity and celebrate Latina/o cultures, a scholar-in-residence for World Outspoken, and a co-host for the forthcoming podcast From the Underside. He’s also writing a book on Critical Race Theory with IVP Academic.

Articles like this one are made possible by the support of readers like you.

Donate today and help us continue to produce resources for the mestizo church.